Across Europe into Germany

Dad's World War II story continues from D-Day until the end of the war.

After a longer gap than I intended, this post completes my father’s account of his adventures as a surgical technician in the European Theater of Operations in World War II.

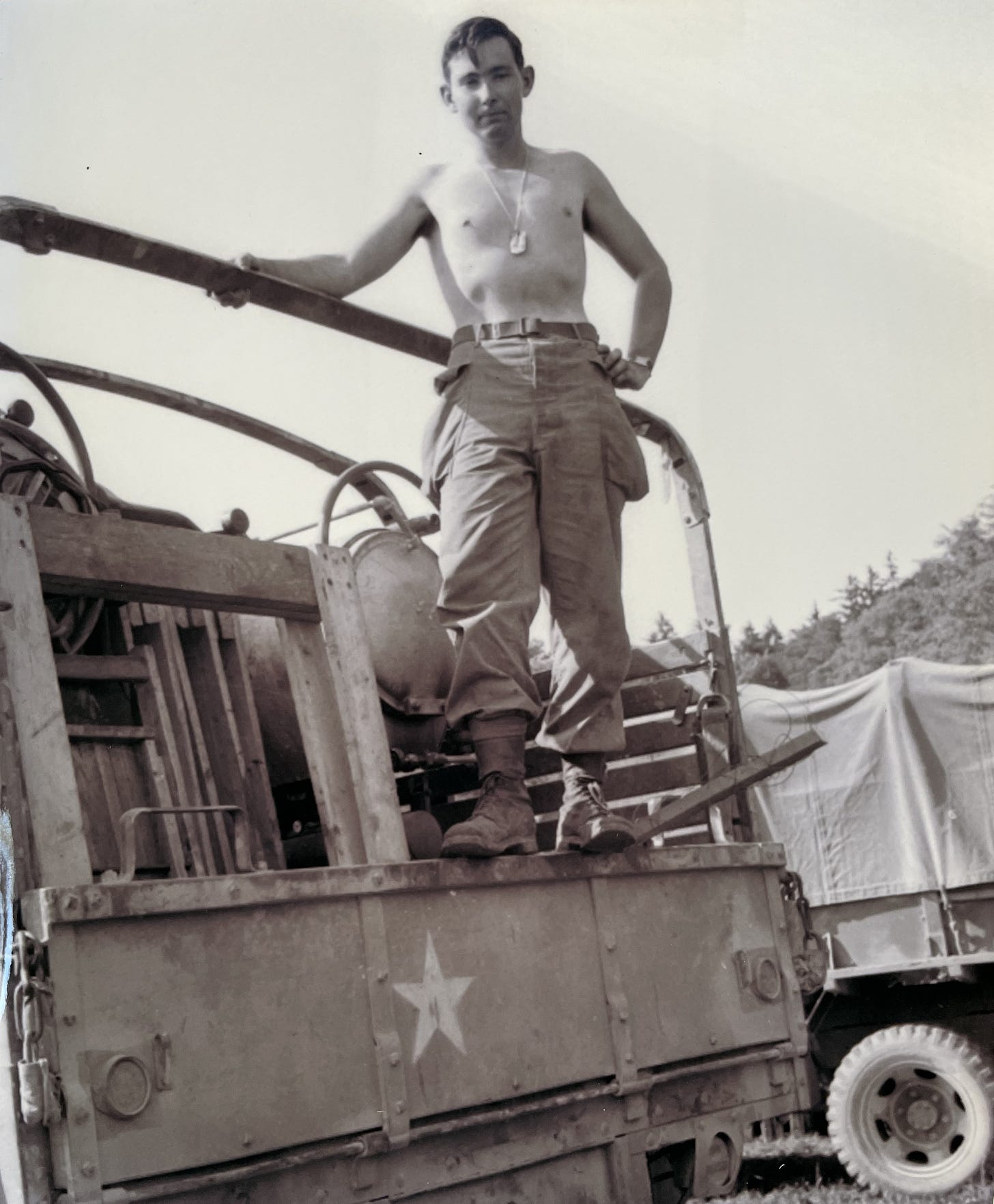

Now age 99, James K. Sunshine enlisted in the Army in 1943 during his freshman year of college and was assigned to the 42nd Field Hospital, Third Platoon. He and I developed this two-part narrative together, drawing on his prior writings and interviews. The first post covered the period from his enlistment through the D-Day landing in Normandy (see From Ohio to Utah Beach). In this final post he traces his platoon’s movements through France and Belgium into Germany, where he witnessed the war’s end in Europe on May 8, 1945.

Battlefield surgery

We did three types of wounds: of the chest, the abdomen, and the big bone of the leg. Everything else was regarded as not critical. The patients’ litters on sawhorses become the operating tables. We would open up a man’s belly with an eight-inch incision, then go through his intestines and other organs looking for holes made by bullets or shell fragments. Damaged organs and bowel were removed. We used great quantities of whole blood. We had sulfa, which we smeared liberally everywhere, and everybody who lived got the new drug penicillin every four hours. Eighty-five percent of the patients survived, which was the exact reverse of what happened with the same wounds in World War I.

I remember a quiet night, with 60 men fresh out of surgery sleeping on canvas cots. I had drawn ward duty and went from cot to cot with a syringe loaded with penicillin, thrusting it quickly into each man’s buttock. Most of them were too sick to care. I checked IV fluids and suction, gave water, took temperatures, and tried to ignore the steady subdued moans of pain. On most nights, two or three men in each tent would die, and their bodies were placed in a truck that waited outside. Each morning the truck made the trip to Graves Registration, where digging crews buried the dead in temporary cemeteries. Once, we placed a wounded Frenchwoman in the truck thinking she was dead. She woke up and there was hell to pay.

Liberation of Paris

We became efficient at setting up the hospital in two hours and taking it down a few days later as we moved to keep up with the advancing battle line. The landscape around us was littered with half-destroyed tanks and trucks, blasted houses, dead cows, and in the hedgerows and woods, German and American bodies turning black and bloating in the sun.

We kept going that summer of 1944: through Pont-l’Abbé, Saint-Sauveur, Sainte-Mère-Église, and Carentan. Our trucks rolled through the rubble of Saint-Lô, through villages whose streets were lined with cheering crowds who thrust bottles of Calvados and fresh vegetables into our hands. We arrived in Paris on August 28, setting up on the outskirts. We watched the Maquis resistance fighters race by in trucks, firing wildly in the air to celebrate liberation.

Battle of the Bulge and the Siege of Bastogne

By December 1944 we had come a long way: out of Normandy, through northern France to Paris, briefly into the Netherlands, and on to Belgium.

It was getting colder. We holed up for the winter in St. Vith, a small town in the Ardennes surrounded by forested hillsides. Our hospital in St. Vith was a three-story house pockmarked with shellfire, but it was warm and we expected to spend the winter in comfort. The headquarters of the 106th Division, fresh from the States, was also in town, and the division’s rifle companies and artillery were east of town.

We talked constantly of the end of the war, and especially of the new GI Bill. Because I was an Oberlin freshman back home, my Army friends, who never dreamed of going beyond high school during the Depression years, asked my advice: “How do you go to college? How do you pick one out?” I said, “First, you get the names of some colleges and you write and ask them for a catalog.” They did, and along about early December, here comes a mail sack full of college catalogs.

December 16, 1944, was a bright late fall day. The war seemed far away. We had one patient in the entire hospital. But he offered a nervous report: “Something is going on up the line.” He was right. On December 17, I came down to breakfast to find the place full of infantry from the 106th, shaken and terrified. Some had lost their weapons or thrown them away. It was the start of the Battle of the Bulge, when the Germans broke through the line for a last big drive.

The snowy hills around town were beginning to show dark figures coming out of the pine forests. A combat command from one of our armored divisions rumbled through town and up into the hills. Four hours later, the tanks rumbled back, casualties tied to the turrets. A colonel shouted, “If you’re coming with us, come on!” We ran for our trucks and joined his column, leaving the hospital behind. For the first time since June, we were retreating. The roads were jammed. By nightfall we had passed the Malmedy crossroads and settled into a convent at Vielsalm with friendly but fearful nuns. We learned that the Germans had machine-gunned an entire battalion of American prisoners in a field near the crossroads we had passed two hours before. We had narrowly escaped the Malmedy massacre.

The next ten days were a nightmare. Without air support because of dismal weather, we kept falling back, getting lost in the fog, staring at the thick clouds as if we could make planes come by force of willpower. We heard that some officers and enlisted men of the First Platoon in Wiltz had remained with their non-transportable wounded and were captured by the advancing Germans. They were marched into Germany to prison camps. We retreated as far as the town of Sedan in France. Finally, the weather broke and the planes came, wave after wave of them, hundreds and hundreds of B‑17s and B‑24s filling the sky.

Bastogne, a Belgian town on the French border, had been encircled by the Germans. More than a thousand casualties lay in a warehouse under the care of a single surgeon. Blood and plasma were gone. Major Lamar Soutter, a young chest surgeon from Boston, volunteered to be dropped into the besieged town with eight other surgeons and technicians. They were loaded along with fresh blood and drugs into a glider towed by a C‑47 and then cut loose to drift to a snowy field at the edge of town. They performed 56 surgeries in the first day alone.

By December 28, the 4th Armored Division had broken the siege of Bastogne. Major Soutter and his team were given Silver Stars and assigned to the 42nd Field Hospital with us. He and I became friends and spent considerable time together, mixing grapefruit juice and the contents of a five-gallon can of medical alcohol that somehow made its way from the medical dump at Bastogne to the major’s tent.

By March we were in Germany, and on April 13 I was sleeping on the floor of a battered house in Elxleben when someone shook me. “Wake up! Roosevelt is dead, Truman is president, and it’s time for your shift.” The words were a shock. FDR had been president since I was eight years old. I couldn’t imagine the country or the war without him. I’d never heard of Truman.

Ohrdruf and Buchenwald

As the war wound down and we pushed deeper into Germany, the secrets began to show. We sent a medical detail up to Ohrdruf, where a camp had been discovered. They returned with pictures and stories of opening the camp to find it full of starving men and heaps of corpses. They had forced the mayor and a group of citizens from the nearby town to walk through the camp, and all the locals said they knew nothing of what went on there. At Buchenwald, we entered the camp to find more corpses, this time of guards caught by the liberated prisoners before they could escape. We walked through the barracks, staring at naked skeletal men on their wooden bunks.

Rhine wine and pickles

By the time we reached Pfeffenhausen, near Munich, it was clear that the war was ending. The Germans we saw now were mostly old men and 14-year-old boys barely able to carry a rifle, and we had few wounded to work on. Major Soutter wanted to see Munich, so he ordered a weapons carrier and off we went. The city was chaotic. Crowds filled the streets, looting the bombed-out remains of buildings: Germans, Americans, British, and French, along with displaced persons from a dozen countries and inmates from the concentration camps in their striped uniforms.

The major spotted a line of people going into the cellar of a bombed hotel and emerging with bottles of wine. He halted the truck, then ordered the rest of us to join the line and wait for our turn in the cellar. I led the way. At the bottom of the stairs, I saw in the dim light hundreds of bins reaching to the ceiling, each with dozens of bottles of Rhine wine. I climbed to the top and handed down an armload of bottles to each of my friends.

In the truck we found we had no corkscrew. Major Soutter, a graduate of Harvard College and Harvard Medical School, knocked off the top of a bottle by striking it against the side of the truck. As we started for the hospital, I saw a man in concentration camp garb coming out of the cellar with a two-gallon jar of dill pickles. The US Army does not run to dill pickles in wartime, and I had a powerful homesick hunger. I offered him a pack of Lucky Strikes, pointed to the jar, and off we went, eating pickles and drinking Rhine wine from broken bottles.

The results were predictable. I woke up in a field near the hospital sometime the next day, desperately sick. Someone had stolen several German chickens, which we cooked over a portable sterilizer stove. A stream of Allied soldiers newly liberated from German prison camps walked aimlessly down the highway: Americans, British, Indians, French. We shared our chicken and the remains of the wine with them. It was May 8, 1945. The war in Europe was over.

Postscript

Eighty years have passed since my father went to war. A retired newspaper journalist, he has written and recorded several reflections on his wartime experiences. He has had some sharp words for current politicians, as well. In 2004, a year after President George W. Bush sent US troops to invade Iraq, chasing after fictional weapons of mass destruction, Dad wrote a commentary titled “Sixty Years beyond Honor”:

Today is the sixth of June, 2004. Three days ago I turned 80. Sixty years have passed since that frightening day I spent off the coast of Normandy, watching those less lucky than me storm the German defenses and eventually win a foothold that within a year would carry us deep into Germany. . . . Today, three days after my 80th birthday, the country I do, indeed, love because it is a good country, stands before the world claiming the right to wage something new for us called “preemptive war,” shredding our freedoms at home and our young soldiers’ lives abroad for reasons few really understand or believe despite what they say, issuing orders that no one is to see bodies being brought home as if, somehow, they are unclean, paying civilian mercenaries to do our fighting for us without a thought for what happens when those mercenaries come home with their M‑16s, making war a profitable game for corporations with friends in a White House whose occupants have never seen a real war close up and whose version of the truth seems to shift from day to day.

Documents, photographs, and audio recordings of Jim Sunshine’s World War II experiences are housed in the Oberlin College Archives in Oberlin, Ohio. Some of his published and recorded reflections include:

“A young man’s war.” Rhode Islander magazine, May 29, 1994.

Veteran’s testimony: James K. Sunshine, 42d Field Hospital. WW2 US Medical Research Centre.

“Sixty years beyond honor.” Providence Journal, June 6, 2004.

On the D-Day landing beaches, our dead were not “losers.” Providence Journal, September 9, 2020.

Kendal at Oberlin Stories: World War II. YouTube, May 22, 2021. The interview with my father starts at minute 8:54.

Text and photos © James K. Sunshine.

I remember the war. The last picture, of your father in Schweinfurt, struck my heart. I was an American Field Service exchange student there in 1953. Many of the buildings were still war-damaged. Your father's recollection of the war reminds us how horrible it was and how courageously those who fought it carried on.

Thank you Cathy for this post... A remarkable story really...

Regards from France