From Ohio to Utah Beach

My dad is among the last World War II veterans. Here is his story.

Most of us in our third age spend some time looking back. We can’t remember everything, and we probably don’t want to, but certain pivotal events remain etched in memory. For my father, it was his service as a medic in World War II. For my husband, it was his childhood in an interracial cooperative in the Mississippi delta in the 1940s and ‘50s, at the height of segregation. These experiences shaped their values and the course of their lives. In my next few posts I’ll share bits of their stories with you.

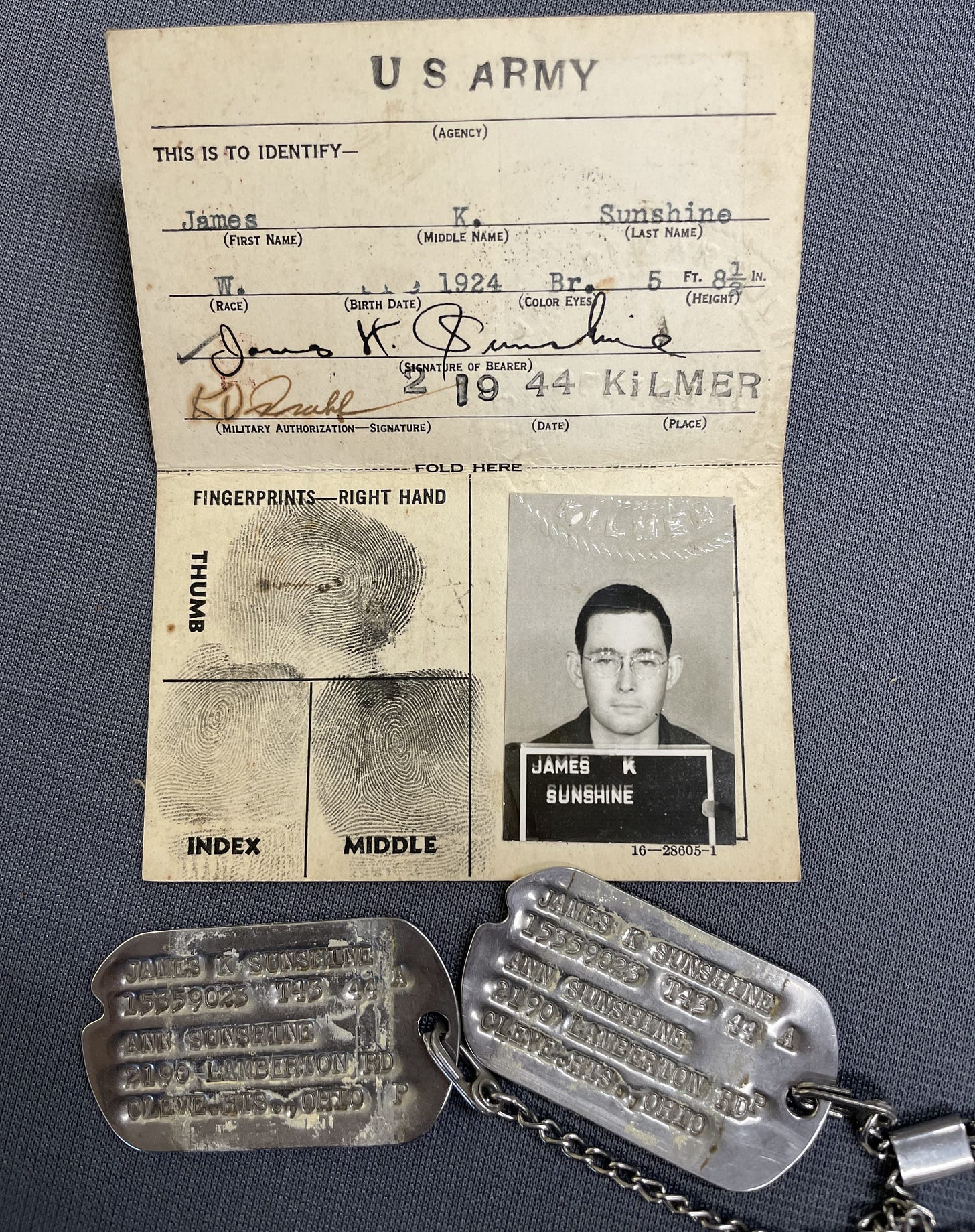

My father, Jim Sunshine, age 99, is one of about 119,000 surviving veterans of World War II (out of 16 million Americans who served in that war). He was a surgical technician with the 3rd Platoon of the 42nd Field Hospital and was part of the D-Day landing on Utah Beach. His platoon ended the war near Landshut, Germany, after escaping St. Vith during the Battle of the Bulge. He writes, “I had the good fortune to be a surgeon’s assistant in a forward field hospital, back from the line just far enough to avoid getting shot, but close enough to feel that I was part of a huge war machine that could never be defeated. Though it was not my doing, I seemed fated to be on the edge of many of the great moments of that part of the war.”

The vignettes below are in my father’s words, drawn from his writings and from oral history interviews I recorded with him. I’ll divide the narrative into two parts. This post covers the period from his enlistment through the D-Day landing, and the next post will describe his unit’s movements across Europe until the end of the war. These are snippets of his richly detailed memories; a full account would be too long for this space. Documents, photographs, and audio recordings of my father’s wartime experiences are housed in the Oberlin College Archives in Oberlin, Ohio.

Enlistment and training

Oberlin opened my eyes, because I had never been to a college. Neither of my parents had ever been to a college. I had to learn fast how things were and how to behave, and I did. But by the end of my first semester, in fall 1942, the war was heating up and everybody was leaving. So I signed up for the Enlisted Reserve Corps and left college in the middle of my freshman year, in the spring of 1943.

I was sent to Camp Grant, Illinois, for basic training. We learned how to march, beginning at two in the morning. Get up, put on a full pack, and march 20 miles. There were endless hours of close-order drill, so that later, when a lieutenant says march up the hill, you march up the hill, even if you get killed. At Camp Carson, Colorado, where I joined the 42nd Field Hospital, we learned basic medical skills and how to put up surgical tents. They were 60-foot canvas tents, each weighing 350 pounds, and it took six men to put one up.

In the fall of 1943 we loaded our trucks and ourselves aboard antique railroad cars with signs saying “Do Not Shoot Buffalo from the Windows” and made the trip back east. We landed at Maxton Army Air Base in North Carolina, where we learned how to load the field hospital onto CG-4A gliders. These unpowered craft, made of pipes and canvas, were meant to be towed behind a C-47, then cut loose over a landing zone. They were to be used going into France. I looked at the gliders we had loaded and said, “I don’t really want to go in that goddamn thing to France. I’d much rather go in by boat.” But nobody asked me.

We were sent to Fort Lee, New Jersey, for embarkation. While waiting in Fort Lee, we could get passes to go across the river into Manhattan. So we all went into the city to the Taft Hotel, where I sidled up to the bar and began drinking. I knew nothing about mixed drinks, but I was going to find out. Eventually we got on the bus to go back to Fort Lee. I was sitting next to the first sergeant, a fearsome fellow we called Sergeant Sam. He was a miserable bastard. At some moment, all of that booze got to be too much, and I puked right into the first sergeant’s lap.

Learning about rank

We crossed the Atlantic in a convoy of ships, protected by Navy destroyers. Once ashore in Glasgow, we were put in a transit camp with dozens of Nissen huts made of sheet metal. In the middle of our hut was a small coal stove. On my side of the stove, I had white soldiers from the South, about 15 of them. I was in charge. On the other side of the stove were Black quartermaster troops, who were already there when my unit arrived.

The white soldiers said, “We ain’t going to live in no fucking huts with no fucking blacks.” Both groups looked ready to rumble. I was 19 years old, I didn’t know what to do, and I was scared. So I said, “Yes, you are. You go on your side of the stove, and these guys will go on their side of the stove, and we’ll live together for as long as we have to be here.” They did it, because I was the corporal. One of the most important things you learn in any military service is that rank is vital. You outrank the person below your rank, and you can order that person to do your bidding, and you must do the bidding of the man with the rank above yours.

“Affectionately, Joan”

Eventually we went on down to Bromyard, a small market town in the English Midlands, to prepare for the invasion of the continent. England had become a vast dump of soldiers, tanks, trucks, and guns dropped on a green and pleasant land that was rather short of things to eat and drink. If one more truck or Sherman tank or 105 mm howitzer was brought from the States, it was said, the island would surely sink.

We were in Bromyard for three months. One day I followed a path past a garden shed and found an overgrown grass tennis court, a garden, and a girl digging in the flowerbeds. She was very pretty. I asked, “What’s your name?” She replied, “Joan.”

Joan and I became friends – perfectly chaste friends, because she was a nice girl. She was an evacuee from Birmingham, living with her Aunt Emo in the relative safety of Bromyard. Occasionally I was assigned to guard duty, but instead of walking around watching for Germans, I often sat beside their coal fire with a mug of tea, talking to Joan. One day I begged some gas from the motor pool, and Joan and I loaded it into a clunky old power mower and mowed the tennis court. I put the net up, and she brought some flour from the kitchen to mark the court lines. Then we played a set of tennis and had tea on the court, and I went home to bed.

Next morning we were told to get up: we’re leaving. The three platoons of the 42nd Field Hospital lined up with full packs, bedrolls, steel helmets, and duffel bags. People from the village stood watching us, waving farewells. A village boy ran along the ranks calling my name and presented me with an engraved calling card. On the back was a message: “Emo and I again wish you the very best of luck and send you our address. Au revoir, Joan.” I stuffed the card into my pocket, threw my duffel bag into one truck, and climbed into another.

Joan wrote me several times during the next year, always signing, “Affectionately, Joan.”

On the eve of D-Day

Sent to a town in southern Wales, we were kept behind barbed wire in a vast encampment, waiting for the war. The weather was foul, mud was everywhere, and the air was heavy with the smell of burning coal. The motor pool people were kept busy changing the trucks, jeeps, and ambulances into amphibious vehicles by extending exhaust pipes above the presumed depth of the beachhead water and smearing waterproofing gunk all over the engines. Someone painted our duffle bags with three parallel yellow bars to identify our beachhead destination: Utah.

There was one reason to be grateful: our orders had changed. Instead of going in on gliders, we would land in boats. We were taken to the port of Barry on the Bristol Channel, where men, trucks, and guns waited on the wharves to board freighters and transports lying bow to stern at the piers. We loaded, then waited for days. Finally we steamed down the channel, heading for Land’s End. The long, slow-moving columns were escorted by patrol craft protecting the convoy’s edges, with barrage balloons tethered to the ships to thwart any diving planes. Below the deck of our Liberty ship were tanks, guns, trucks, and men packed into narrow pipe berths stacked five deep. Someone told me that in the bottom hold were 100 trucks loaded with 105 mm artillery shells.

The officers passed out a printed message from General Eisenhower. “Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen of the Allied Expeditionary Force!” it began. “You are about to embark upon the Great Crusade, toward which we have striven these many months. The eyes of the world are upon you ...”

Utah Beach

On June 7, 1944, our ship anchored off Normandy. Around us scores of ships waited to unload as landing craft plowed back and forth to the beach. Guns fired constantly and smoke rose from the beach and from further inland. At night the rocket barges fired toward the battle, the long fiery stream of rocket tails arcing into the sky.

On June 8 we climbed down nets and a gangplank to a landing craft. With the beach more or less secure, we marched past fields marked with signs in German warning of mines and littered with crashed gliders. Our major, an unpleasant, self-important surgeon who imagined himself a paratrooper, ignored his map and led us inland until suddenly we were surrounded by mortar bursts. Diving into ditches, we heard infantry in foxholes shouting at us to get down and questioning our sanity. We retreated, cursing, wishing that the major actually was a paratrooper and somewhere else.

We set up four tent hospitals. Wounded men, tagged for identification, lay on litters in rows as ambulances arrived with fresh loads. Most were American paratroopers of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions, but some were Germans, who were given the same treatment as Allied casualties.

I dug my foxhole beside a hedgerow and reported to a tent surgery. A surgeon, a major, noticed me standing uncertainly and said, “Let’s go, corporal, get some blood on your hands.” I followed him through the blackout curtain into the surgery, where three teams were at work. Generators outside the tent provided power for lights. I was told to hold a leg while a surgeon sawed it off. I wondered why I didn’t throw up.

At one point I was pressed into service as an anesthetist. Two surgeons, a captain and a major, were operating on a seriously wounded man. I placed a mesh mask over the man’s nose and mouth and began pouring ether from a can onto the mask. The captain said, “Take him deeper,” meaning pour more ether. The major said, “Let him up a bit.” I was puzzled at the opposing orders from two officers, both my superiors. In the army, you do what you are told or you end up in the stockade. I made a quick decision to obey the officer with the higher rank, the major.

Later I was sent with a wounded German to an isolation tent. He had gas gangrene, a fatal infection that flourishes in damaged flesh. I was supposed to stay with the German until he died. There was nothing I could do to help him except give him water. I couldn’t speak his language beyond yes and no and does it hurt. And he couldn’t speak mine, except to moan and say “ja.” He was young, blond, and filthy dirty, and his wounds exuded the foul odor of gangrene. The night sky was lit by flashes of artillery fire and a German plane buzzed overhead, drawing anti-aircraft fire, which fell back on us as shrapnel. I stared at the German boy, not knowing what to do. Finally, toward morning, he died.

To be continued. Text and photos © James K. Sunshine.

Fine writing, Corporal Sunshine! Amazing recall of detail. Impressive that you were a medic. So glad your daughter got you to write of your wartime experiences.

Thanks for this. Very interesting to read this personal account from your dad!