When I started this blog, I knew that writing would be part of my third age. But it couldn’t be the kind of writing I’ve often done, writing to promote political activism – or at least it couldn’t be only that. I needed to do something different.

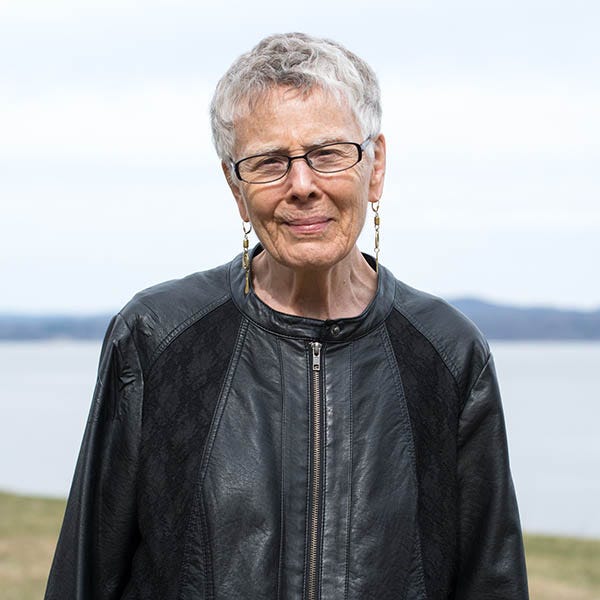

Last fall Bill and I visited an old friend, Gail Hovey, and her wife Pat Hickman in their home on the Hudson River. Like Bill, Gail has a long history of activism in the US civil rights and anti-apartheid movements. She co-founded Southern Africa Magazine in the 1960s and was managing editor of the journal Christianity & Crisis. With Bill Minter and Charlie Cobb, she co-edited No Easy Victories: African Liberation and American Activists over a Half Century, 1950–2000. Now 83, Gail’s still writing, as I would expect. What I didn’t expect to hear is that she has delved into two new genres: memoir and poetry.

This intrigues me – not that I would try to do such a thing myself. I could no more write poetry than I could fly. But I wanted to hear from Gail why she has chosen this path. How can writing, of whatever kind, help us make sense of our past and continue our work in this stage of our lives?

CATHY: Gail, in the holiday letter that you and Pat sent out last year, you mentioned the book Evening Land by the Swedish writer and Nobel Prize winner Pär Lagerkvist. One poem in the collection begins, “At the journey’s last halt, in the house of evening, bread is broken . . .” You said the phrase “in the house of evening” resonates because you are living in that house. You wrote, “It comforts me to think this way. I have mostly visited Sweden in summer, when the evening lasts a very long time.”

GAIL: Pat and I have espresso every afternoon and read a poem. In winter, we sit in front of the fire for this daily ritual. “The house of evening” seemed like a good way to acknowledge that we’re not young anymore, we can’t do everything we used to do, and we can’t do a lot of things that we want to do. Fortunately, we’re both healthy. But friends are having to move into assisted living, having strokes, heart attacks, knee surgery, shoulder surgery. This year, 2023, has been astonishingly full of it. One ends up doing more caring of one’s beloveds, friends and family, than ever before. In Sweden the days are very long in summer. But they also have long winters when it’s quite dark, and that may be something we’re having to deal with.

Why we write

CATHY: Your letter went on to say that you started writing poems after the birth of your granddaughter in May 2021.

GAIL: Giuliana was born in Belgium, and I was sad that I might not get to see her very much. So I started writing poems to her. At some point I’ll make them into a collection to give her when she’s older. My poems will tell her about me and our family, things she couldn’t know otherwise. I’m also writing poems about what’s going on in the world. Writing poetry is necessary for me now, but it’s scary. You can only write what’s inside, and if it’s shallow, if it’s irrelevant, if it’s insensitive, it’s all right there! Yet I find that when I’m writing, I feel more alive.

CATHY: I started my blog during the pandemic. It was scary, as you say. I spent nights not sleeping, debating whether to undertake this. I was afraid to fail. I was afraid I’d either bore people with impersonal writing, the kind everyone’s inbox is already full of, or else reveal too much of the personal. I didn’t think I could find a middle ground.

Now I’ve been writing it for almost two years, and it feels like a part of my life. There was a month-long gap recently when I didn’t post anything. I was having difficulty coming up with topics. I felt stuck. And I was surprised how much I missed writing it. I missed it intellectually, as a way of thinking about things. I missed it emotionally, and I missed it physically. The act of writing – thoughts in head, fingers on keyboard: it absorbs me in a way that other things don’t. When I’m having a sleepless night, if I replay in my mind words I’ve written, it calms me. This was a revelation: that having found the courage to launch this thing, I now need to do it.

GAIL: That’s totally believable.

CATHY: Have you published any of your poetry?

GAIL: I’m starting to submit poems for publication and will continue to do so, but it’s a slog. You submit to 100 publications, and if you’re lucky, one poem will be accepted. I don’t want the work it takes to publish to overwhelm the actual writing of poems.

CATHY: There’s a difference between writing for ourselves and a circle of friends, which is how the blog started, and writing – publishing – for a larger public readership. How you make the leap from one to the other, whether you want to make the leap from one to the other, and what exists between those two ends of the spectrum is fascinating to me. I do find that writing the blog has enlarged my networks and enabled me to communicate with friends I may not see often, or ever.

GAIL: I would love to have a big audience for my poems. I’m interested in taking language seriously and learning more about poetry, finding a way to say clearly what it is I need to say. Children’s book writer Kate DiCamillo asks, “How do we tell the truth and make the truth bearable?” That’s also my question. If I’m able to do that, yes, I want my work read.

But that’s not why I write. I write for myself, because I need to. Sometimes I share a poem or two with my closest friends because I want them to get what I’m going through or to appreciate something that has moved me. That’s a real pleasure. I will probably always struggle with questions about the value of my work. Who cares about it? Does it matter who cares? As I get older, I hope I worry about that less.

Writing as a lens on the past

CATHY: I’m interested in how we use writing to reflect on our life experiences. I’ve written two blog posts on my time in Niger with Peace Corps, and one post about returning to Providence, Rhode Island, where I grew up. I also interviewed a friend – you know Adwoa – who recalled the road trips her African American family took in the 1950s, during segregation.

GAIL: As you know, I published a memoir in 2020. It’s titled She Said God Blessed Us: A Life Marked by Childhood Sexual Abuse in the Church. The epigraph for my memoir is a quote from Adrienne Rich. In her poem “Toward the Solstice,” she writes, “I am trying to hold in one steady glance / all the parts of my life.” That’s what my memoir was trying to do.

CATHY: That line aptly describes the work I’m doing, also, trying to make sense of my life through writing. The disparate pieces can be made to fit together only with effort. I’ve always assumed that other people’s lives somehow were more orderly and better planned, without false starts or questionable choices. That may be true for some people, but perhaps not for most?

GAIL: I think one of the values of memoir, in prose or poetry, is that it gives the lie to the common notion that other people’s lives are more orderly, freer of anxiety, more generous, etc. My memoir explores the long-term impact of childhood sexual abuse and how that impact manifests in ways that one might not expect. I wrote it for several reasons. The person who abused me was a woman, and almost nothing has been written about such women. I was tired of secrets. Writing the memoir made me an honest woman in the world for the first time.

CATHY: You started your memoir in your sixties and finished it in your seventies. You’ve said, “By this time in my life not writing would have been far more difficult.” Why is that?

GAIL: I think that everyone needs to be seen. We want people to understand who we are. In movements for Black empowerment and civil rights, for example, part of what’s behind that is “See us for who we are and what our real-life experience has been. Don’t look at this through a white lens or a patriarchal lens.” It’s the same with LGBTQ people and especially trans people now.

I’m trying to hold all the parts of my life together. The process of writing about this deeply fraught relationship in my youth helped me understand it at a different level. And people who have read the memoir and have talked to me about it have made me think that for some people reading it had value.

Poetry and action

CATHY: You have a lifetime of experience as an activist – in East Harlem, Southern Africa, Hawai’i. How do you get from there to the more personal writing you’re doing now?

GAIL: It was a challenge to give myself permission to write poetry. I had this notion that, with all the political work that needs to be done, what am I doing writing poetry? But I realize that’s a silly dichotomy, because very personal poems can have public meaning. One poem I wrote is called “For My Granddaughter, Giuliana” (see below). I wanted to send a picture postcard of a bison to her. Simple enough. Except that the text on the postcard was so objectionable – white men and Indians – that I almost couldn’t send it, and the poem had to say why.

CATHY: Circling back to the theme of necessary writing, why has poetry become essential to your activism in this stage of life?

GAIL: If I don’t take care of myself, I have nothing to give to anyone else. Do you know Audre Lorde’s famous essay, “Poetry Is Not a Luxury”? It starts out:

For women, then, poetry is not a luxury. It is a vital necessity of our existence. It forms the quality of the light within which we predicate our hopes and dreams toward survival and change, first made into language, then into idea, then into more tangible action.

Lorde goes on to say that action in the now is also necessary, always, and she combines action and poetry. How I or anyone can do that is the ongoing challenge. How do I keep myself sane by writing what I need to write? And be the partner, friend, and family member that I want to be, and also be a good citizen? What does it mean to be good citizens in this time? I will continue to struggle with all this.

CATHY: I will, too. Thanks so much, Gail.

For My Granddaughter, Giuliana

I’d like to send this postcard to Giuliana

like the ones Pat sent her grandsons

which gave me the idea

I’ll have to get more postage

she’s in BelgiumWe’re visiting in Kansas

the postcard pictures bison

state animal and on the back side

words of explanationThat’s the rub

The text says

Before the white man

settled KansasWhite man

Not white people

white pioneers

white settlers white

adventurers white

colonizers white

land thievesThe text goes on

the buffalo provided

the Indian with

everything he neededThe Indian

The Arapaho

The Cheyenne

The Comanche

The Kansas

The Kiowa

The Osage

The Pawnee

The Wichita

The Cherokee

The Chippewa

The Delaware

The Iowa

The Iroquois

The Kaskaskia

The Kickapoo

The Munsee

The Ottawa

The Peoria

The Piankashaw

The Potawatomi

The Quapaw

The Sac and Fox

The Shawnee

The Stockbridge

The Wea

The WyandotteGiuliana isn’t

even nineteen

weeks old yetLighten up

I tell myself

mail the cardShe’s coming

will live nearby

we’ll learn names

play games

dress up go down

into the woods

together

Thank you Cathy for interviewing my good, good comrade, Gail. It was an important reminder to all of us..that writing, reflection, poetry, memoir, essay..all are part of the struggle...Na Gode

I love that both of you are making sense of the world by writing about personal things , of your own and others Thank you ! I use plants and gardening to connect with people all over the world Turns out gardeners are a very political group of people ( Who knew?) I now have gardening friends in England, Canada , New Zealand , Uruguay, and Iran etc ( Sharing pictures of family etc with only a few)