Road trip with a difference

A friend remembers a childhood both like and unlike my own.

Last summer I wrote about my family’s early camping trips (see We traveled in style. But whose style?, September 22, 2022). A friend of Bill’s and mine, Adwoa, commented that my post sparked memories of her own family’s road trips from California to Oklahoma when she was a child. Their travel, like ours, featured a dad at the wheel trying to beat his best drive time, kids counting license plates and scuffling in the backseat, and sandwiches by the roadside. But there were differences. My family stayed in campgrounds and motels and ate in restaurants when we felt like it. Her family could do neither, because they were African American and it was the 1950s. I asked her to tell me more.

CATHY: In the 1950s, my family drove all over New England and Canada in our old Plymouth station wagon, staying in campgrounds. And in the summer of 1965 we drove across the country, coast to coast. So road trips were a big part of my childhood, but it never occurred to me to ask what those trips might have been like if we’d not been white. Would they even have been possible? So I thank you for making me think about that, and I’d love to know more. Can you tell me a bit about your family, and then describe the trips you took?

ADWOA: I grew up in Northern California, in Richmond, next to Berkeley. I’m the first generation of my family to be born in California. My parents were from Sapulpa, Oklahoma, near Tulsa. Their parents had migrated from Louisiana and Texas to Oklahoma, and my father was born in a Black town, in Boley, Oklahoma. My parents moved from Oklahoma to California at the beginning of the war to find work and to escape Jim Crowism, looking for a better life. But our grandparents and other family members stayed in Sapulpa.

“We never spent the night anywhere”

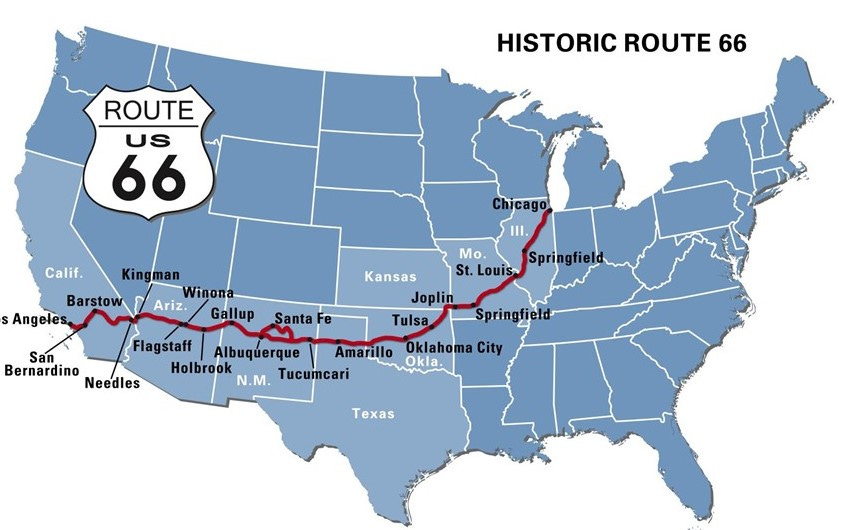

ADWOA: From the time I was around 10, my parents would drive us to Oklahoma to spend the summers with our grandparents. It was exciting. We had a big car. My father did almost all the driving, even though my mother was a driver and later on had her own car. We packed lunches for a couple of days, and then we would begin our trek from California to Oklahoma on Route 66, through Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas.

CATHY: Was this the 1940s, 1950s?

ADWOA: I was born in ’44, so it was the 1950s.

CATHY: What route did you take?

ADWOA: We went south toward Los Angeles, then inland through Bakersfield and Needles and into Arizona. Route 66 took you through Flagstaff and Amarillo. It’s beautiful country. The Bay Area is a lot of water, and the Southwest was different because it was so arid. We stopped at national parks. We went to the Painted Desert. We would stop at Indian trading posts, where we always had friendly conversations. We’d buy food at grocery stores and then stop at a park or along the road and have sandwiches. I have a couple of pictures of us by the side of the road, my brothers with their little hats on.

CATHY: How many brothers?

ADWOA: I had two younger brothers. They remember trying to count the number of cacti along the road, and naming the license plates. One of the things I thought was similar to your description of your trips is the family bonding that came from us being in the car for about 40 hours straight.

CATHY: I’m not sure you’d call what my brother and I did in the back seat bonding. I mean, occasionally my parents had to pull the car over.

ADWOA: Well, my brothers, they weren’t bonding either. In fact I used to sit in the front seat so my mother could sit between them.

CATHY: Where did you spend the night?

ADWOA: That was the difference. We never spent the night anywhere.

CATHY: Just drove straight through?

ADWOA: My father drove straight through. He’d be timing himself, so he would say things like, “Well, we made it in 36 hours this time!”

CATHY: How could he do that?

ADWOA: He would stop on the side of the road and sleep for an hour or two. Sometimes my mother would drive for an hour, and he would sleep while she was driving. It was never longer.

CATHY: So no motels, no campgrounds, no nothing.

ADWOA: No, none of that.

CATHY: And was that because he preferred to drive straight through? Or was it because he knew you wouldn’t be welcome?

ADWOA: You know what, for years I thought my father was a maniac on those trips, because he was nonstop driving, and he never complained. He just drove. And we’d be like, “Can we stop? There’s a motel! Can we stop there?” I thought he was just being a macho guy, wanting to get there quick. I was in college before I realized there was no place to stop. I mean we couldn’t. The bathrooms were not even available.

CATHY: Were there signs that said you couldn’t go in, or you just knew?

ADWOA: I think he just knew. As a kid I didn’t pay any attention. I think there probably were signs, I just didn’t see them. Our parents totally sheltered us.

ADWOA: Some years we’d drive to Oklahoma in the winter to spend Christmas with our grandparents. On one trip it was cold, it was icy, and my father decided, okay, let’s stop. So we stopped by the side of the road and they got the blankets and pillows out. Those cars were huge. They had big trunks and lots of space. Everyone was asleep and I was in the front seat because my mother was in between my brothers in the back. I was the first one to wake up, and I was like, “Is this snow?” I was about 14 and I’d never seen snow, you know.

CATHY: As you drove between California and Oklahoma, did you notice a difference in the way people reacted to you? Were the Indian reservations more cordial?

ADWOA: Yes, they were. My father had a great personality. He talked to everyone. I remember him trying to get us to try some snake that had been prepared in one of those trading posts. He was like, “It’s so great! Come on, guys!”

CATHY: What, snake that you eat?

ADWOA: Yes!

CATHY: Hmm, no.

ADWOA: And I’m like, no. My mother was like, no.

CATHY: But he was open to it.

ADWOA: He was open. Yeah.

CATHY: Sounds like a great guy.

ADWOA: He was very open, and he was a great guy.

“We don’t have those signs in California”

CATHY: How did you perceive the differences between your grandparents’ home in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, and your home in California?

ADWOA: Sapulpa was a segregated town. All the Black people lived up on the hill, totally separate from where most of the white population lived. My father and mother went to segregated schools. I remember when I was about 13, I was with my grandmother in Sapulpa and we had gone downtown. I asked, “What does that sign mean – ‘Whites only’?” And she said, “What, you don’t know what that means?” I said, “We don’t have those signs in California.”

CATHY: Did your parents talk to you about any of this? Or did they assume you’d eventually figure it out, and you didn’t need to be burdened with it now?

ADWOA: That’s it exactly. They would say things like, “People of all races can be nice or mean. And you do not judge people by their color, but by what they do and don’t do to you. And yes, there’s a lot of segregation when we go to Oklahoma. But people still have a good life, and you have to accept it as a good one.” That’s my parents. My grandmother, on the other hand, was always very clear. She wanted us to understand that it’s not all rosy. People have a hard time because of racism. I would say, “I don’t understand. If I was living here, I would just go and drink the whites-only water.” And she said, “No, you would not. Because I wouldn’t want you to be lynched or beaten.”

CATHY: So she had a different perspective on what you, as children, needed to know than your parents did?

ADWOA: Exactly. I think she realized that our parents would take a different tack, and she didn’t think that was good at all. She thought children should know, because people get hurt when they don’t know. In hindsight, that’s probably why we hardly ever went downtown in Sapulpa to shop. It’s not like we would go and buy clothes, which I later learned from my cousins you couldn’t try on. You could buy it, but you couldn’t try it on.

CATHY: Because it would touch your body.

ADWOA: Yes. My cousins who lived in Sapulpa, we would talk, and they gave us more insight than our parents did. They would say, “You California people don’t know anything.” I used to think they were just talking about rural life, because we had cousins who lived on a farm. My uncle owned the farm, he grew peanuts. But now I'm sure it was about more than that – about rural life and segregation, too.

CATHY: This is so interesting, because I can read books on civil rights history and it’s still abstract to me. But hearing the personal experiences of somebody I know, that makes it real.

“I began to understand it in more depth”

ADWOA: For the greater part of my early years I remembered our road trips as being just such a great time, not understanding why my father drove for 40 hours straight. It wasn’t until I was in college, in the mid-’60s, that I began to understand it in more depth. That segregation was about more than just not being able to drink the water.

CATHY: I think many of us in our third age are looking back, piecing together our life experiences to see what they add up to. How did your family’s travel shape your thinking, your understanding of the world?

ADWOA: It gave me a sense that the United States was a broad place, a big place. Diverse in people and in the ways that people live. In 1978 Ed and I drove across the country with Omari, our youngest, from Berkeley to DC. We took the same route, Route 66, and it was so much fun. Some things had changed, but it all looked familiar, and some of those trading posts were still there.

CATHY: I hope you stayed in motels this time.

ADWOA: Yes, we did!

CATHY: Have you ever thought of writing about all this?

ADWOA: I’d like to write something so that future generations will understand just a little bit more. I think, for African Americans especially, there are so many gaps. Some of it has to do with slavery, and some of it just has to do with people not wanting to look back. Maybe it was too painful. I have a niece whose daughter is trying to write something, and we've talked about it, and we're trying to find pieces of our family history. So maybe she will be able to write that story.

Thank you both from me too. Very emotion AND thought provoking. Cathy's question about whether Adwoa had considered writing about these experiences led to another: Have you BOTH considered writing more of these "vignettes" as you did this one - together? The ordinary details described so well - siblings squabbling and playing car-travel games in the back seat, dads being dads, kids' growing awarenesses, etc all make these wonderful windows that make vivid the so-same/so-different realities we all experience on this same continent. They can be timeless, "political-less" ways of seeing, understanding, feeling, that I think can be valuable in this era of seemingly narrower and narrower seeing and understanding.

Thank you both! That brings back alot of memories for me too. Of course, our family vacations were road trips. We visited most of the national parks in the US and camped there. They were amazing in the 50s, clean and not very crowded. You could always find a camping place if you arrived early enough.

As far as segragation, I at least, was totally unaware of what was happening as we grew up in rural Mississippi. I went swimming with the black kids on weekends but we had to take a bus to town to go to school. I was envious that they got to stay and go to school on the farm. TOTALLY unaware of the fact that they did it since they didn´t have a choice. With all the racial tensions swirling aournd, I happily picked berries, went swimming, without knowing the townspeple were so upset about ¨mixed bathing¨ I think it was just as well I didn´t know what was happening. We grew up without really knowing that peole were judged by the color of their skin. Obviously that wasn´t a choice if you were black. I went to church with Lula, the woman that took care of me since both of my parents were working. I had a great time singing along with the choir and liked their church much more than our boring one. Unfortunately, my kids grew up in Mexico and learned about racism. Here everyone is judged on the color of their skin. The more European blood you have, the better. Though very hypocritcally, the culture of the Aztecs and Mayas is honored. I am happy to say that in Washington State, my grandkids are TOTALLY unaware of racism also. Which goes to show you, it is something that is taught.