The letters box

I dreaded the task. Then I tumbled in.

It’s true, though I can hardly believe it: Bill and I are moving, most likely in September. I’ll say more about where and why in a future post.

Meanwhile, we’re downsizing – again. We did this three years ago when we sold our house, but things started accumulating again, as things do. Then there are the stubborn downsizing problems that I never did solve but just deferred, stashing the items out of sight in a basement storage cage.

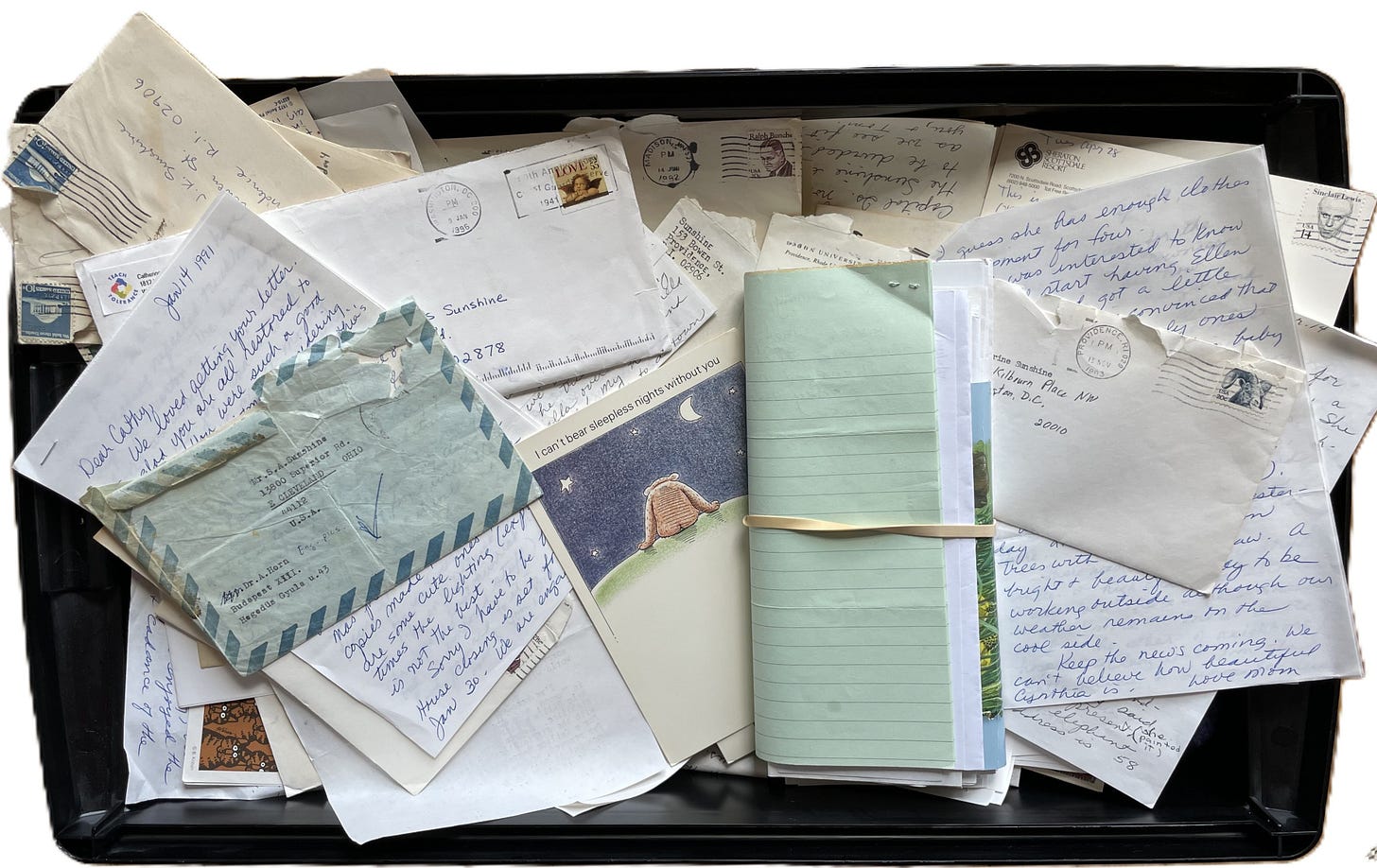

The scariest of those is the letters box, actually a plastic bin. Growing up in the pre-internet age, I sent and received handwritten letters regularly – as did most people – and for some reason I kept them. They cover a period from the late 1960s to the late 1990s, by which time email had largely taken over. (In February 1999 my father began using email and wrote, “The thought of our exchanging messages within a few minutes is absolutely beguiling.” My mother lay stricken with cancer in a downstairs bedroom, leaving my father homebound – except when a health aide visited – but unable to do anything to alter the downward spiral; she would die in March. With no family living nearby, email became his emotional lifeline.)

For years I avoided opening the bin, fearing what I might find. Letters are primary documents. They offer a view of the past that is not unfiltered – obviously the original writer’s filters are at work – yet is free of the biases of those who come later, seeking to interpret and explain the past. Letters also bypass the protective filters of memory. Imagine the psychological stress and sheer mental exhaustion if we could remember every moment of our lives.

But I did open it. And once I started reading the letters, I could hardly put them down.

Fatherly advice

Much of the collection consists of letters from my parents, especially my mother. A reserved and private person, she wasn’t much given to emotional sharing. She died when I was 45, and I regret not having gotten to know her more deeply, as one adult to another, when we still had time. Yet when I reread the letters, I hear her voice, feel her presence. I gain new insight into the person she was.

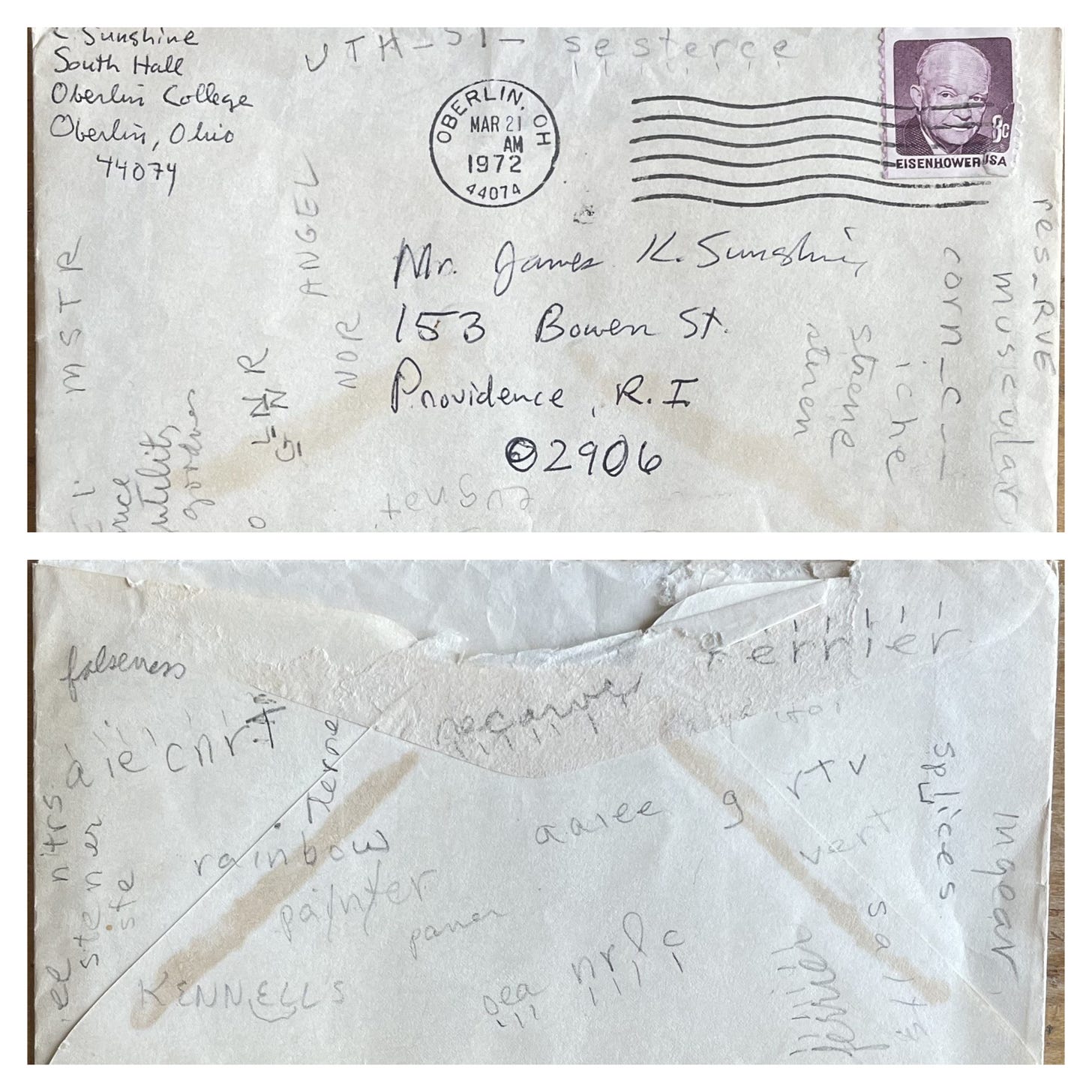

Even envelopes bear witness. In 1972, as a college freshman, I wrote to thank my parents for some camping equipment. The note natters on about dropping a class, coming down with a cold, and the bad weather in Oberlin, but what interests me is the envelope, which my mother had evidently used as scratch paper. Brilliant and introverted, she liked to work what my father, in his eulogy, described as “extraordinary and complex puzzles ... whose instructions I could not even begin to decode.” The envelope is covered on both sides with hieroglyphic markings, and I can see my mother even now, alone at her desk, jotting notes as she cracked the code.

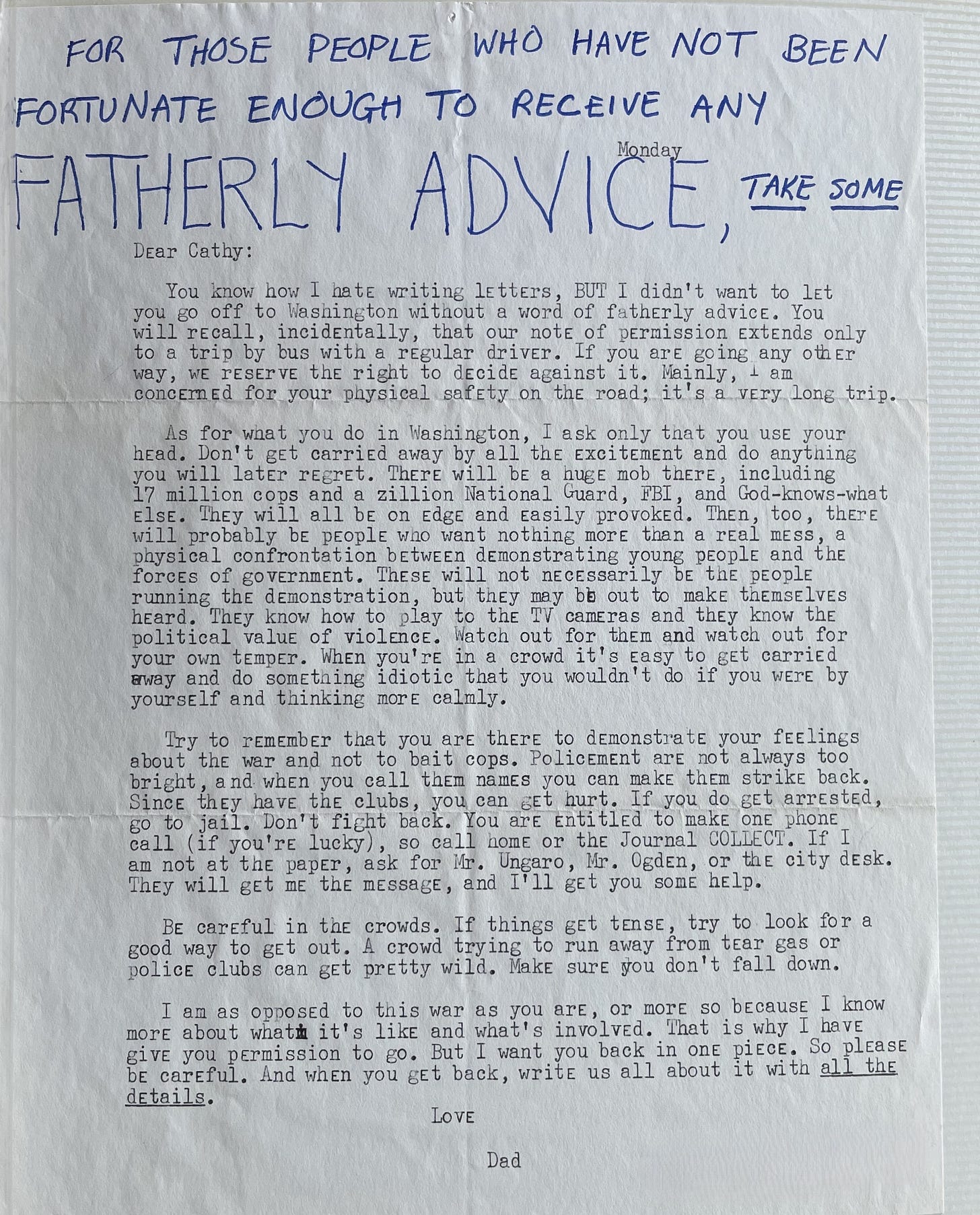

My father often wrote with advice. One such missive arrived when I was about to travel to Washington, DC, with some friends for a big march against the Vietnam War, my first. This may have been 1969 or 1970, when I was 16 or 17. He urged me not to provoke the cops or fall in with outside agitators. If I got arrested, I was to call collect. He concluded, “I am as opposed to this war as you are, or more so, because I know what it’s like and what’s involved. That is why I have given you permission to go.”

He weighed in on my early career choices, and these letters are hard to reread. In 1982, working for an activist group in DC, I wrote a book about a left-wing movement that had seized power in a small island nation. I interviewed people in the country and imagined my work to be a well-researched look at a successful revolution (as the ruling party styled its takeover). But almost everyone I interviewed was allied with the government, which put us up in a hotel, and the flattering portrayal I produced was little more than PR. A few years later the ruling clique shattered amid violence, proving the short-lived experiment to have been neither successful nor particularly revolutionary.

My father, the journalist, was skeptical of this attempt at scholarship. “My eyebrows go up when I hear you say things without equivocation that I doubt you can back up with hard evidence. Perhaps I am wrong and you really can, but I would like to be shown. ... I have spent most of a lifetime learning to be careful about accepting what people tell me, especially when what they are saying is self-serving. That is why I worry when I think you are accepting as fact what people say merely because you admire their objectives. ... You have to ask the hard questions, not just the questions you know will bring the answers you want.”

Dad, if you can hear me, out there in the beyond: You were right. And I eventually learned.

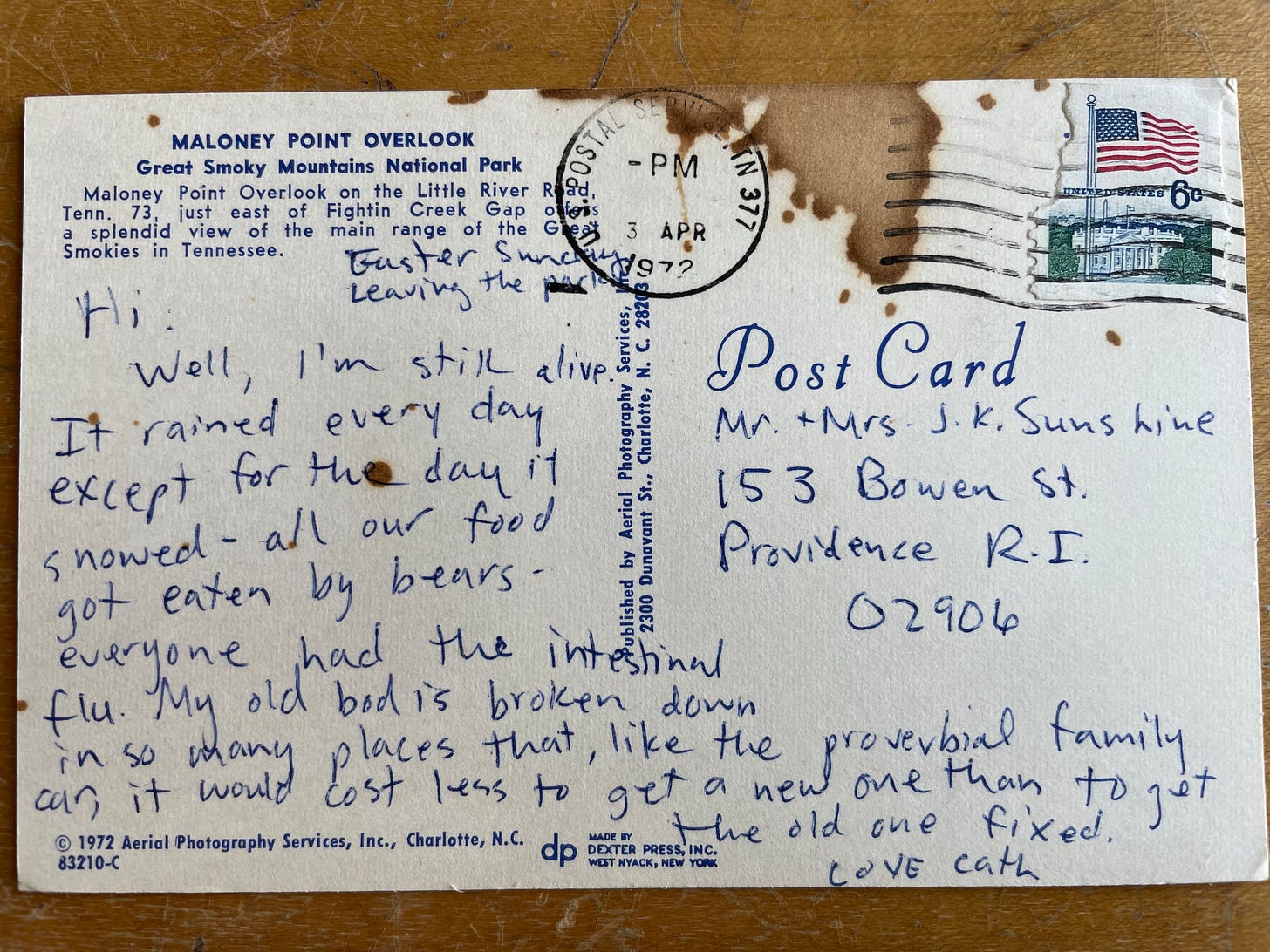

I also wrote letters to my parents, some of which they saved and later returned to me. A postcard from my first backpacking trip, in the Smoky Mountains with college friends, describes a miserable outing: “It rained every day except for the day it snowed. All our food got eaten by bears. Everyone had the intestinal flu.” Another hike featured an “attempt to cross a raging torrent of ice water in the nude.” I doubt it was a raging torrent, a phrase probably intended to alarm my parents, but we were in fact naked, hiking boots strung by their laces around our necks.

My early writing is larded with superlatives and clichés. A thing is not just beautiful but “truly beautiful”; an apology is a “heartfelt apology”; my confessed ignorance, “breathtaking ignorance.” I could be smart-alecky. “Dad,” I wrote, “I’m ashamed of you. ‘Girl publisher,’ indeed. I only hope you don’t allow your newspaper reporters to get away with value-loaded identifiers like that.” (Despite my admonitions, my father continued to use terms such as “lady lawyer” for the rest of his life.)

The bin contains correspondence with friends dating back 40 or 50 years. They include people I barely remember as well as a few I’m still in touch with. (Hi, Sonia!) There are letters from old flames and would-be flames. “Those three days together have left me in something of an emotional turmoil,” one wrote. “I felt very deeply that there was something good between us and am now sad that all this must pass.” There was also a lengthy apology from an early crush who worried, decades later, that he’d taken advantage. I wrote back immediately, assuring him that I bore no hard feelings and that my own teenage immaturity had been equally to blame. In matters of the heart, I could be snippy. Writing from college, I complained to my parents that a former boyfriend was “coming up this weekend (not at my invitation) to have some kind of a heart-to-heart talk that he feels will resolve things in his mind. I’m unclear as to what kind of doubts he could be having at this point. I wonder if he’s ever heard of letting something die naturally.”

What to do?

The letters testify to a formative period of my life. Events I remember vividly, dimly, or not at all: they happened, and here is the proof. With their wealth of detail, the letters fill in some of the mental white space around my fragmentary memories and the snapshots in albums.

But the bin is heavy and bulky to store. If I don’t deal with these letters now, whoever cleans up after me will have to face the task. That would likely be my daughter Cynthia. Even if she keeps them, what happens a generation or two down the road? If I were famous, the letters could go to an archive. I am not. The sensible thing to do would be to dispose of them now.

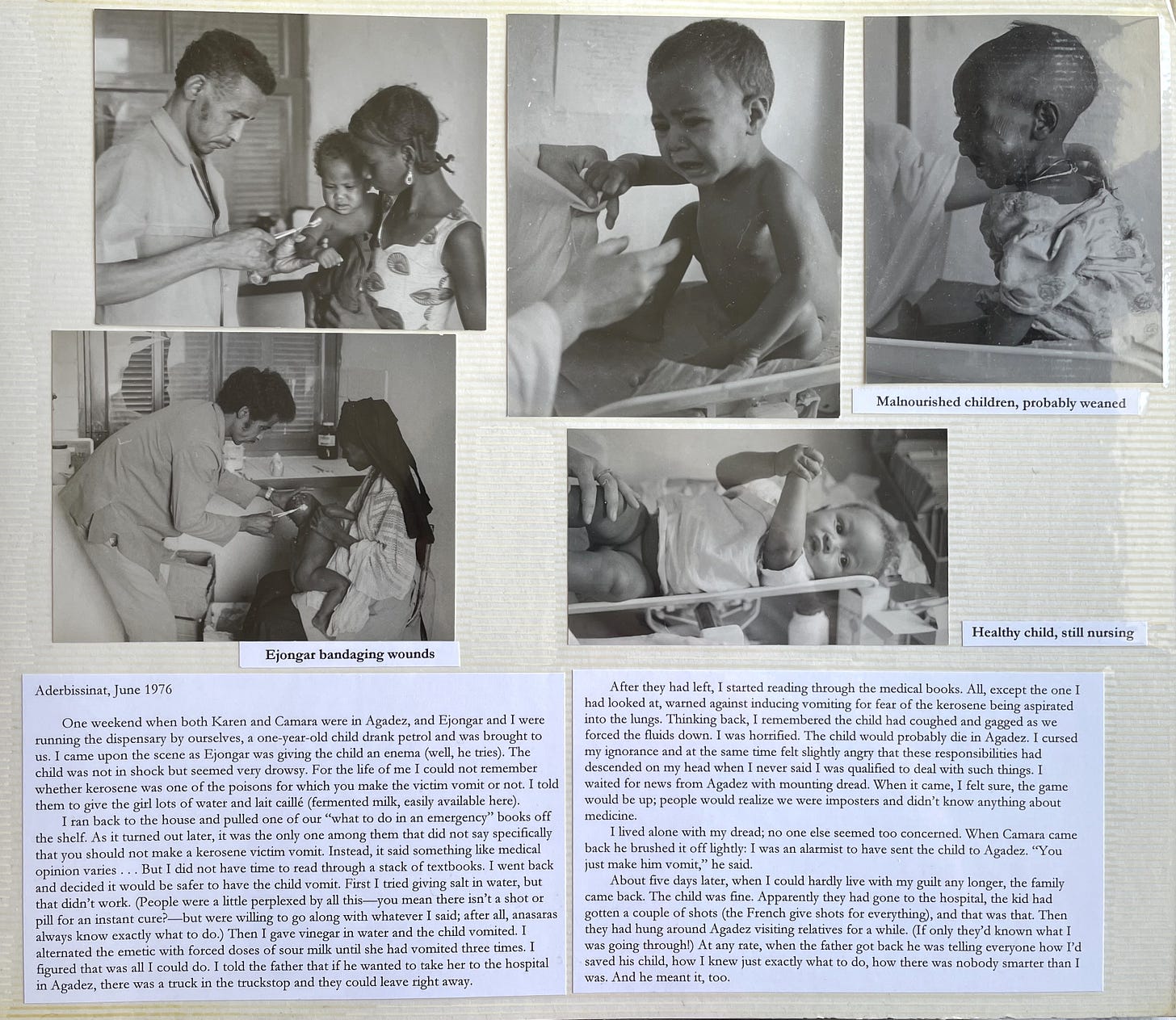

I can’t do it. Instead, I’m triaging. More than half the collection has already hit the recycle bin, mainly correspondence with people who didn’t end up playing a significant role in my life. I compiled my letters from Niger, where I served two years in the Peace Corps, into an album, along with photos. An album on a shelf invites casual browsing; a storage bin in a basement, not so much. I’m keeping the letters from my parents, at least for now. In 2000, after his bereavement and a major surgery, my father wrote, “Dear Cathy, Thank you for everything you have done. You and Tom are the greatest kids in the world. Mom would be so very proud. Love, Dad.” How can I throw this away?

I’m also keeping cards and letters from Bill and Cynthia. Like most millennials, my daughter grew up using email and text, but there’s a bundle of handwritten letters she sent home from nature camp at age 11 or 12. How homesick she was that first summer! But she toughed it out, finished the session, and returned to the camp for many summers after that, eventually joining the staff. The letters detail every hike, every sleep-out, every frog and owl and snake she encountered. I know she will want to keep these letters. I will save them for her. And the cycle starts all over again.

This sounds like me - I have two large drawers filled with letters, from WWII (my father and uncle), between my grandparents and parents, and so many from me during college and later. They look just like yours, still in envelopes, and the paper beginning to disintegrate in some cases. I plan to organize them and hopefully type up some of them to share with family members. Thank you for sharing your own experience dealing with these family treasures!