“The border is now the entire country ...”

My neighbor, a retired priest, has shared life with migrant communities for 40 years.

Note: It’s been a while since I’ve posted, but my excuse is a good one! My grandson Dylan James Lane was born in March and I’ve just returned from Toronto, where I ran errands and fed cats while my daughter and her husband wrangled their newborn. Grandparenting is a joy.

Twice a month, a queue wraps around the brick plaza in my neighborhood as needy residents, mainly immigrants from Latin America, await a Catholic charity’s distribution of fresh fruits and vegetables. On a recent morning several of us worked the line, handing out small red cards with advice on what to do if federal agents knock on your door. “No abra la puerta, no conteste ninguna pregunta, no firme ningún documento sin hablar con un abogado,” I suggested, following the text on the cards. Don’t open the door, don’t answer any questions, don’t sign anything without talking to a lawyer. I ran out of cards quickly. People are scared.

And not without reason. Just last week, immigration agents showed up at a nearby elementary school and tried to detain the school nurse. School personnel asked the agents for a warrant; they didn’t have one, and left without making an arrest. But elsewhere in the city and its suburbs, ICE has taken people away.

Doing crosswalk duty outside my neighborhood school, I got to chatting with a fellow volunteer, Mike Seifert. While my efforts to support immigrants have been sporadic, Mike has worked closely with migrant communities for four decades, first on the southern border and now from his home in DC. I asked him how his work has changed under Trump and how his own perspective has evolved in this stage of life.

CATHY: When did you start working on the border?

MIKE: I was ordained a priest in 1986 and went to work in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. People had moved to the area after a dam project flooded their lands years earlier, and now they were living alongside the Pan American Highway, a major drug trafficking channel.

I worked with an Australian priest and three North American nuns, and I quickly realized that we were not much help there. People would come to the parish and say, “They took my son. Can you help me get him back?” I didn’t know who “they” were, or what kind of language to use for offering kidnappers the expected bribe. Also, we were there on tourist visas, so we knew we could be removed at any time. We started looking into doing projects along the Mexican border, and in 1989 I moved to Harlingen, Texas.

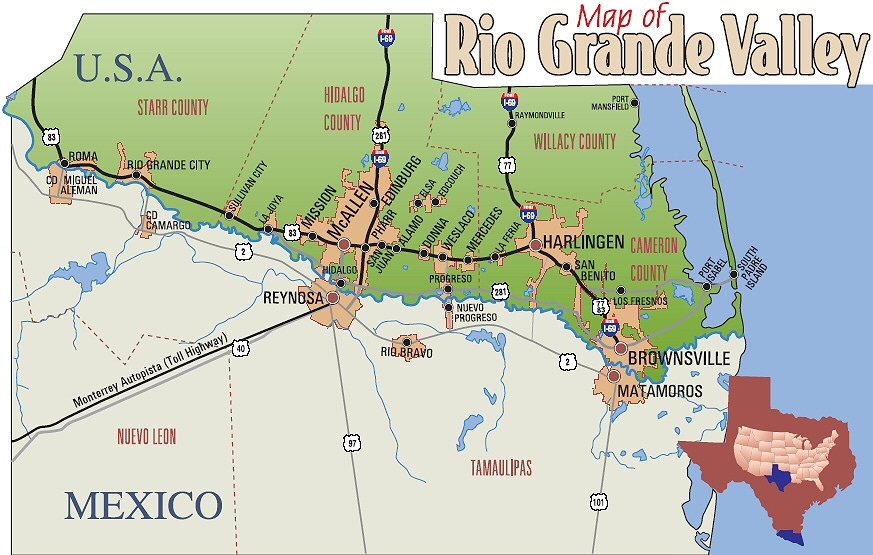

I worked with three populations: residents of the Rio Grande Valley, at the southern tip of Texas; Mexicans who lived in Matamoros, a city just across the Rio Grande from Brownsville; and people passing through the area after crossing the border. Among the latter were Guatemalans, Salvadorans, and Nicaraguans fleeing the Central American wars. They were being described as “terrorists,” with President Reagan warning that the Sandinistas were “just two days’ driving time from Harlingen.”

My first task as a priest there, besides pastoral work, was helping people apply for asylum in the United States. Again, I found myself doing something I wasn’t prepared for. But people needed help, and they couldn’t afford to pay a lawyer. I stayed in the Rio Grande Valley as a priest until 2009. It’s the poorest region of the country apart from Indian reservations, and I loved working there.

I met my wife, Dr. Marsha Griffin, in 2008, when she was a pediatrician at a community health center in Brownsville. We were collaborating on an elective for medical residents, helping them understand how to advocate for their community.

CATHY: You had left the priesthood by that point?

MIKE: I had taken a leave of absence to help my dad nurse my mom, and I realized that I was being offered the gift of a family. I felt at peace leaving the priesthood after 24 years of service. And so I married and was blessed with the treasure of my wife.

Organizing along the border

MIKE: In 2009 I started working with the Rio Grande Valley Equal Voice Network, supported by the Marguerite Casey Foundation. I coordinated the work of 12 local organizations that were active in poor communities on both sides of the border. They helped people build social and political power by turning out the vote, showing up at county meetings, and advocating for issues like education, health care, and housing. I was the “network weaver,” working with the powerful Brown women who ran these grassroots organizations.

We came up with some interesting projects. The most vulnerable people were the domestic workers, the maids. They didn’t have papers. They’d be paid next to nothing, and subjected to abuses. The only time we could get them together was Sunday Mass, because the employers would let them go to church. I would say, “We need people to help prepare a breakfast for after Mass.” It was an excuse to get them together, away from their bosses.

Over time that became a working group, and they developed a model contract for someone who’s going to work in domestic service. One member objected that employers would ignore such a contract, but a wise woman pointed out that there were many new wives who had no idea how to organize a house or work with a maid. “This is how we teach them – and protect ourselves.” The group grew to about 250 people and got linked into a national domestic workers coalition.

Family separation under Trump

MIKE: By 2017 I had taken a position with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of Texas. Trump had just been elected, and I was charged with tracking conditions on the border and organizing responses. We decided to start a simple project, courthouse witnessing. At the first hearing we attended the courtroom was packed with defendants. They were all being charged with “entry without inspection,” a misdemeanor that previously had almost never landed someone in federal court. But Trump’s Attorney General Jeff Sessions had implemented a zero tolerance policy. At the end of the first hearing, the judge asked if there were any questions. A woman shouted out, “Where are my children?”

We discovered that the federal government was separating children from their families. The parents would be taken to court, and while they were in court, the children were declared “abandoned” and taken away. Working with the Texas Conference of Churches, we spread the word that the US government was, essentially, kidnapping children. A couple of months later – not soon enough – the policy ended.

But the Trump administration continued to target asylum seekers. The ACLU of Texas asked our team to take testimony from people camped out on the Mexican side of the border. The stories were astonishing. One woman told us, “Two weeks ago, people showed up at our house in southern Mexico and told me they wanted to put my 11-year-old daughter on layaway. I said what does that even mean? The guy says, ‘Well, my 13-year-old son likes your daughter. When she comes of age, he’s going to buy her. So we’re putting her on layaway.’ I’m like, no, we’re not doing that. The guy says, ‘Okay, you know what happens next.’” She continued, “I didn’t understand. But some neighbors said what happens next is they lock you in your house and burn the house down and you all die. So that very afternoon we sold the 45 chickens I had just bought, and a brand new refrigerator. And I came to the border.” She added, “If you turn around carefully and look under that light post over there, you’ll see three men. They’re part of that game. They’ve come here looking for us.”

It was one story after another. People were desperate, but also hopeful. We’d ask, “Why are you coming to the United States?” And they would say, “Because we trust you.” Thank you. Thank you for that.

Beyond the border

MIKE: In 2021 our daughter, who lived near us in Brownsville, moved with her young children to DC. About six months later, we woke up and realized we didn’t have any family anywhere near. So we decided to move.

I’ve continued my work from DC, both remotely and through border visits. Toward the end of the first Trump term, a coalition of advocacy groups set up “welcoming committees” along the border from Brownsville to San Diego. I work with the Brownsville committee. We coordinate by Zoom, bringing in various groups – Doctors Without Borders, the ACLU of Texas, the Texas Civil Rights Project, and others. Our committee has helped many asylum seekers reach some bit of safety, despite the opposition by both Biden and Trump. We also provide remote support to shelters in Matamoros and Reynosa.

CATHY: Both those cities are on the Mexican side?

MIKE: That’s right. Matamoros is the twin city to Brownsville, Texas, and Reynosa is the twin city to McAllen, Texas. For example, one of the women running the Reynosa shelter told us recently, “The washing machine and the freezer broke. And we’ve got 200 people here to feed and clean up after.” So it was my job that day to put out a call to our mailing list of a couple thousand people. Get the money, but also find somebody who could buy the darn thing and bring it to the shelter. A week later, she sends pictures. “Hi, thank you. Here’s the freezer. Here’s the washing machine.”

CATHY: How do you see your practice evolving in Trump’s second term? Given that people are not coming across the border, but ICE is ramping up actions inside the United States.

MIKE: There’s no one crossing the border now. You see the activity shifting away from the immediate border to the interior. The border is now the entire country. We’re trying to figure out what the next steps are. We’ll continue to focus on harms to children, especially children in detention. In addition to our work with the welcoming committees, my wife and I help run Community for Children, which seeks to cover gaps in medical care for migrants on the border and across the country.

I also volunteer with a group called SAMU First Response, which helps asylum seekers and migrants in the DC-Maryland area. We do little practical things: drive somebody somewhere, get furniture. I do marriages. Did one yesterday in Takoma Park, Maryland. The marriage was performed in the back of my car, which was a bit odd, but it was freezing cold and sleeting. The couple was grateful and gracious and lovely. They came from a small island off the coast of Venezuela, so we talked about seafood, and they waxed nostalgic. Here, they have no job and very little hope. They’re desperate, but talking about home seemed to make them feel better. And seeing that spark of life is a quick way past all of the numbing statistics.

The power of informal resistance

CATHY: Have you changed your practice as you’ve grown older?

MIKE: As anybody in the third age realizes, you know a lot of things. And one of the important things is that it’s often good to keep your mouth shut and listen. And pick a moment to say, “Oh, I’m not so sure.”

If everybody in a meeting speaks Spanish, you can say, “Please do the meeting in Spanish. Don’t do it in English because it’s not going to be as effective as you think.” If you have a group of well-meaning, smart, passionate people from both countries, the language and the tenor and the weight of the meeting will always go to the United States. In our Zooms I advocate for the Mexican members of the group. I translate for them and urge them to speak up. They’ll have important information that needs to be known, but the Americans are talking over them, so I interrupt. The Americans on the call are really fine people. They don’t intend to do this, but it’s just the nature of those kinds of meetings.

If somebody asked me, what is the attitude you most appreciate at this point in your life, it’s going to be gratitude, but gratitude in the sense of being able to pay attention to the moment that you’re in. And what helps that attention? A mother or dad or a neighbor who’s worried, and they trust you enough to speak about that. If you’re involved with a family, a community of people, it grounds you.

Since I’m retired and no longer employed by an institution, I don’t have to get my comments screened by anyone. I don’t have to go before somebody’s board and worry about affecting our funding. That’s a liberating thing. There’s a lot of power in informal resistance. This is what people across the world have struggled with, and now it’s our turn. So it’s an interesting moment for sure.

Great post...

Great post and an inspirational man. Thank you!