"Not as scary as it seems"

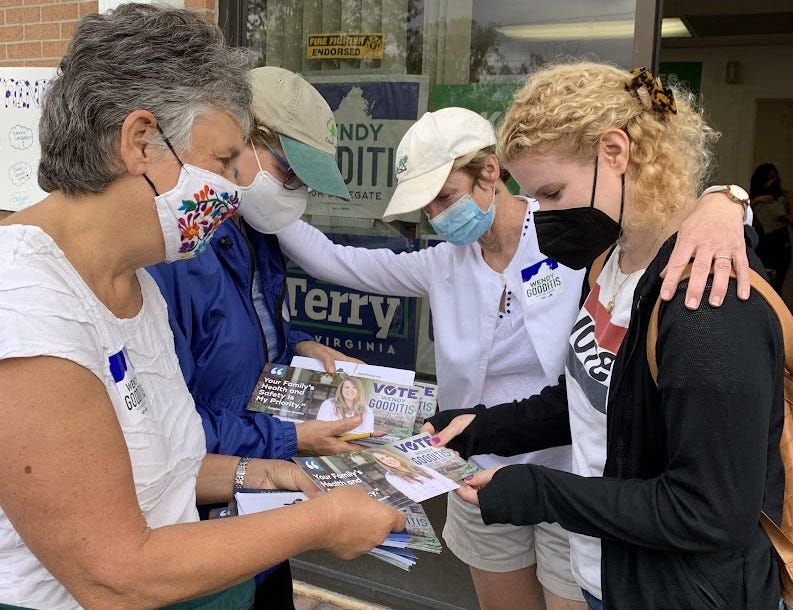

Ahead of the midterms, three women share their canvassing stories.

The 2022 midterms are two weeks away, and if you’re like me, you’re worried. Republicans aim to take over the US House and quite possibly the Senate. Just as concerning are state-level races. State legislatures around the country are rife with MAGA extremists and 2020 election deniers. Now, many more of them are running to occupy statehouse seats and secretary of state offices, where they’ll control the counting of votes for the 2024 election.

It’s not too late to act; indeed, the last two weeks are critical. Many of these races are close. And talking with voters, face to face or on the phone, in the days before an election can be decisive in close races.

How hard is it to chat up strangers about politics in this polarized age? Not as hard as you might think, according to three friends I asked. We’re all volunteers with NOPE, a DC grassroots group whose members are knocking on doors in battleground states. Our conversation focused on the experience of door-to-door canvassing rather than on how to do it, but there are links to resources at the end.

CATHY: How did you all come to be knocking on strangers’ doors?

DEBBIE: I've been politically active my whole life. I started canvassing with my father, who was a precinct chair in the suburbs of Chicago. Later I worked for the Communications Workers of America, and about 20 years ago labor started having members knock on doors of fellow union members. So I was always canvassing through the union political program. After I retired I became involved with NOPE. I kept coming to canvasses, and they asked me to work with Liz to co-lead this season of canvassing.

LIZ: I, too, am a long-time canvasser. The first person I canvassed for was McGovern, when I was in college.

CATHY: Me too!

RENEE: I was never involved until the Hillary campaign in 2016. A friend asked me to go to North Carolina with her and get out the vote the weekend before the election. And obviously the election didn't go well, but the canvassing was so much more fun than I had realized it could be. My first thought afterward was why didn't I do more? I don't have a right to complain if I'm not willing to do anything. So in the 2018 midterms I canvassed in Virginia. For the 2020 election I only made phone calls, which I didn’t like as much as face to face. I had some great conversations on the phone, but people are more likely to be unfriendly when they don't see your face, I think.

CATHY: Renee, is knocking on doors different than you expected?

RENEE: It is. I was intimidated the first time. But I was surprised at how willing people are to talk, even just to say “I don't really follow politics.” We ask, “What's on your mind?” You can start all kinds of conversations. People have said repeatedly, “I'm so tired of the ugliness, I'm so tired of the polarization.” And we've encouraged people to vote, even when we found out they weren't voting our way. We're not, you know, angrily stomping off. And right now, when people explicitly say “I'm so tired of the fighting,” to have someone be polite to you who doesn't agree with you is really nice. So I find it easier than I ever thought it could be, and more uplifting and encouraging and interesting. It's just not as scary as it seems.

Memorable encounters

CATHY: Do any particular moments stick in your mind?

DEBBIE: I remember knocking on the door of an African American family right before the 2008 election that Obama won. The entire extended family had come to that home to have a pre-election dinner to prepare for what was, for them, the most exciting day – voting for an African American. That was fun.

CATHY: I was canvassing in York, Pennsylvania, for the 2016 general election. A man came to the door who didn’t speak much English, but when I switched to Spanish he was happy to chat. The whole family is voting, he told me. Yes, voting for Clinton. But his wife, from another room, called out to object: “No, no, la mujer!” The woman! And the man and I reassured her together: “Clinton es la mujer!” Clinton is the woman.

RENEE: I remember canvassing in Virginia in 2018. And this woman was going to vote for the Republican incumbent congresswoman, Barbara Comstock. Oh, she was awful.

CATHY: And is now a repentant anti-Trumper.

RENEE: And the voter said, “You know, I'm not a Republican. But when I was trying to adopt my son and I was having problems, Comstock’s office was so helpful. And I'm grateful to her for that.” All I could think of to say was, “That's great, and I can see why you would feel loyalty. But just so you know, she votes with Trump 90 percent of the time. And the woman goes “Ohhhh ...” She was headed for Comstock out of family loyalty, and I hope we knocked her off the orbit. I don’t know.

CATHY: How do you deal with rude or unfriendly people?

DEBBIE: There aren’t that many, to tell you the truth. You say, “Thank you very much.”

CATHY: And walk away.

RENEE: When we were in Pennsylvania recently, my friend remarked to the campaign guy, “I've never had such friendly people as we've talked to here.” And he said, “We've gotten a lot better at targeting whose door we’re knocking on.” The data collection has improved so they have more to go on, helping you find people who are persuadable.

CATHY: Most houses in the suburbs have doorbell cameras. There aren't that many people who open the door and have no idea that it's you standing there. That weeds out a lot of people who might otherwise be unfriendly. They just don't open the door.

DEBBIE: Cathy, I've gotta tell you a story that happened last weekend. I rang the doorbell – it was a Ring video doorbell – and waited a bit. And somebody came on and said, “Hello, who are you?” Ring doorbells, you can answer them on your phone. And I explained that I was canvassing. She said, “Wait a minute, I'll be there,” and she drove from around the corner. And we had a lovely conversation. It turned out she was a very strong supporter, and she gave me a big hug.

I had another conversation in which somebody talked to me the entire time over the Ring doorbell. Never came to the door. This person wanted to know about early voting, and I told her where to early vote. So I've gotten into a habit of holding up my flyer in front of the Ring doorbell. If nothing else happens, they at least have seen it.

LIZ: I had someone – he wasn't rude or unfriendly, but he was totally conservative and started out a little antagonistic. We ended up talking, and he said, “Thank you for doing this. This is what democracy ought to be about. And I’m never going to agree with anything you say, but I'm glad you're here.” So I was glad I had persisted in the conversation.

DEBBIE: Most conversations are very brief. We shouldn’t leave an impression that there are these intense conversations all the time.

CATHY: In 2018 I was canvassing in an affluent suburb outside Manassas, Virginia. And I rang the doorbell of a big house, and a harried-looking woman came to the door. We talked, and she asked what my candidate had done during her time in the Virginia Senate. “Well,” I said, “she helped expand Medicaid in Virginia.” And immediately I thought to myself, what a dumb thing to say. This woman is very well off, and she’s not going to care about that. But her face changed, and she said, “You know, when I divorced I lost my husband’s health insurance, and the children and I are on Medicaid.”

And I thought, wow, don't make assumptions about people. You never know what their circumstances are. One reason I like canvassing is that you get a glimpse of other lives that are unlike your own. It takes you out of your own reality and into other people's, seeing their neighborhoods, their houses, how they live. I find it fascinating.

LIZ: I had one house in a working-class neighborhood in Virginia that was, I think, an education for me. I knocked, and this man came out, and his 10- or 12-year-old daughter was standing next to him. I made my pitch for Clinton. And he said to his daughter, “Can you go back in the house.” Then he said to me, “We're really, really struggling to get by. I'm in construction. I can barely make the house payments. And there's so many immigrants coming in, taking the jobs that I would like to get.”

How do you respond? You can make the academic argument that immigration isn’t what's driving unemployment. But it's also a moment for empathy. He wasn't just being ideologically a Republican. He had thought about this, and he was deeply worried about his family and didn’t want to say it in front of his daughter. And so it was a moment for me to learn.

RENEE: People want to tell their stories. When someone says something inflammatory, if we just nod and say, ”I hear what you're saying,” they come down a notch.

LIZ: I've only once had somebody be rude. I knocked and they didn't answer. They had a “no soliciting” sign. I left a flyer and got back in my car, and he came out of the door and said, “Did you see my sign? You’re trespassing! You can't be here! I'm gonna call the police!” And I'm like, “Yeah, great, fine. We're leaving now.”

Does it work?

CATHY: Do you think canvassing works?

LIZ: There’s research that says that canvassing, of all the different methods of voter contact, is most likely to increase the odds that someone will vote or persuade them to vote for a certain candidate. I believe that someone is more likely to vote if you were friendly and they made a sort of commitment to you to go out and vote. Also, name recognition is important to these down-ballot races. Amazing the number of people that haven't heard of the candidates. So one more time of getting the name in front of them, I feel, makes a difference.

DEBBIE: When I was at working with the union, we were told that people often need seven touches in order to be moved from “I'm undecided” to “I'll vote for this candidate.” So even when people aren’t home or don't come to the door, and you leave a flyer, I figure that's one of the seven times.

CATHY: In 2019 I was canvassing on Election Day in a suburb of Richmond. We were getting out the vote for a Virginia statehouse candidate who was trying to unseat the right-wing Republican incumbent. My voter list showed an older man, a Democrat, living at the address, but no one was home. I left flyers on his door saying “Vote today!” and giving the location and hours of the local polling place. As I walked back up the street, I glanced over my shoulder and saw a car drive up to the house and park. An older man got out with keys in hand and walked to the front door. He saw the flyer, picked it up, studied it a moment – then turned around, got back in his car, and drove away. I can only assume he was going to vote.

The challenges and rewards

CATHY: What's the hardest part of canvassing?

DEBBIE: The first door knock. Once you do it, it's fine.

LIZ: You can have discouraging days when nobody answers, or when you only talk to people at opposite ends of the spectrum. So you could spend an hour and a half and come away saying, gee, I drove all this way, and I don’t think I’ve actually contributed.

CATHY: For me the hardest part is finding a place to go to the bathroom!

RENEE: A challenge, yes, timing your water consumption. Or figuring out how you're going to walk, which route makes the most sense. Also it takes me a couple of knocks to figure out how to not sound like I'm reading a script, how to be folksy and friendly but not like I’m acting. It starts off awkward but then it becomes natural, and surprisingly, you end up having a good time.

CATHY: This question is for those of us in our third age. I love being outside, I love walking. Still, canvassing is tiring. How do you get the energy to keep going for several hours or more?

LIZ: Snacks! I never go out without my canvassing peanut butter and jelly sandwich. I make sure I stop and eat something every half hour or so. And have a hat and sunscreen. Fall canvassing is so much easier than summer canvassing.

DEBBIE: We'll do a packet in the morning, break for lunch, and then a packet in the afternoon. We don't push ourselves beyond our limit. And if people are not walkers, they can team up. One person can be the driver, and the other can get out of the car to knock at each address.

This is what I get out of it. First of all, if you like to walk and you like to be outdoors, it's wonderful. Second, like you said, Cathy, I'm interested in seeing neighborhoods. And third is that I love meeting my fellow canvassers. I’ve made new friends. Liz and I, we've become very good friends through this experience. I hope you'll agree, Liz.

LIZ: Yeah, absolutely.

DEBBIE: Friends who say, “Oh, I'm so hopeless” – I just feel like there's many things you could do. Canvassing is one of them, if it works for you. But do something. It helps you find people who are like you and overcome that sense of hopelessness.

2022 midterm hotspots

RENEE: Does it matter where you go to get out the vote? I hate the thought of driving from here to there when you could just knock on doors in your own neighborhood.

LIZ: It does matter. NOPE tries to figure out the most strategic places to go, and we absolutely think the Philadelphia suburbs are our number one priority for this midterm cycle.

DEBBIE: In this election, Pennsylvania is so important. We've focused on the Pennsylvania House because for the first time in 30 years, there's a real belief that it could be flippable to the Democrats.

CATHY: Because of redistricting?

DEBBIE: Because of a much more fair redistricting in Pennsylvania. We picked three Pennsylvania statehouse candidates who are in districts that Biden won in 2020, but currently an incumbent Republican is in each of those districts. We’re canvassing for Cathy Spahr and Lisa Borowski in the Philadelphia suburbs, and for Sarah Agerton in south-central Pennsylvania. At the same time we're supporting Josh Shapiro for governor and John Fetterman for US Senate. And in Virginia we’re working to reelect two terrific congresswomen who are very, very vulnerable, Abigail Spanberger in Northern Virginia and Elaine Luria in Virginia Beach.

We target candidates who are in close elections and have a chance of winning. We don't canvass for those who appear to be a lost cause, nor do we canvass for those for whom it’s a done deal.

CATHY: Renee, I don't know how much flexibility you have in your job or your life. But what I’ve done several times is I’ve taken three to five days, leading up to Election Day, and gone to a battleground state and stayed. If the local organizers know you're coming, they can sometimes find someone to host you, or you can do a motel. I was in Fredericksburg, Virginia, for the first Obama election in 2008. For the Trump-Clinton election in 2016 I spent five days in York, Pennsylvania, where a lovely local person hosted me. I'm still in touch with her. And I was in Manassas, Virginia, for the 2018 midterms. By staying locally, I didn't have to drive back and forth to DC every day. And I find my comfort level increases as I get familiar with a place and its candidates. So if you have flexibility, you might want to consider staying a few days.

LIZ: Going back to the same place is nice. I do catch myself wondering “Is that a Pennsylvania law or a Virginia law?” when someone asks about, for instance, absentee ballots. If you always go to the same state, you don’t have that issue.

CATHY: Thank you, Debbie and Liz and Renee, for all you do.

To find out about canvassing, phone banking, and voter protection opportunities, some of which can be done remotely, please join NOPE’s email list. Also see my recent post Menu for the Midterms. You can find canvassing events near you on Mobilize.com.

Canvassing Conversations is a training video from Turn PA Blue and 31st Street Swing Left. It shows conversations with different types of voters you may meet at the doors.

A Yale University study found recently that robocalls and blast emails don’t persuade voters; what does work is personal conversations with another human being.