In my last post I described helping my father plant a garden at his retirement community in Ohio. Located in a college town, that community (I’ll call it “K”) is home to many third-age women with liberal to progressive views. I told Dad, I’m interested in talking to women who’ve been activists for a long time and who have managed to continue their activism. He handed me the resident directory, and I skimmed the bios, and Ann Francis caught my eye. She’s a lifelong educator and activist, not to mention a journeyman pipefitter. This was someone I needed to meet!

I’d heard about Ann in the runup to the 2020 election, when Dad joined a group of K residents writing letters and postcards to get out the vote. As the organizer, Ann faced two challenges. One was covid. In March 2020, K, like most senior living facilities, went into lockdown. Residents couldn’t gather. The other hurdle was the community’s policy of remaining apolitical to respect the diversity of views among its residents. You can use common space for political activities, but they must be arranged privately. You can’t use the community’s bulletin boards, website or newsletter to advertise a partisan event. Ann had to figure out how to work within these constraints. Snippets from our conversation follow.

CATHY: I knew you were doing letters and postcards for the 2020 election because Dad got roped into it. I shouldn’t tell you this, but he wrote some very snarky things about Trump in those letters, that he knew he wasn’t supposed to write, and he sealed up the envelopes really quick.

ANN: [laughs] Oh, he probably got some votes. Because the letters were directed toward people who probably would appreciate a snarky comment.

CATHY: I know women who are continuing a lifetime of activism. And I know women who suddenly became activists after the 2016 election. They’re 70 years old, and here comes Trump, and they go, “This is horrible! I have to do something about this!” And they’re knocking on doors the next week.

Seeing ourselves as others see us

CATHY: You were in Peace Corps.

ANN: I was in Malaysia, from 1964 to 1966. I was teaching secondary school students in a Chinese school, and then I was supervising teachers of English. Malaysia had just gotten their independence, so we were the transition group from the British colonialist teachers to the Americans. It was a very interesting time to be overseas and in Asia. We were increasingly aware. I had been influenced by Kennedy and wanted to do something to change the world, but I became much more knowledgeable about my role as an American and the kinds of things that Americans did to not make such a great world.

I was in a town that was principally Chinese. There was tension between the Chinese and the Malays, who were the majority population. I would call it racism, and we would talk about that in class. And the students began challenging me because so much was happening in this country around civil rights. They said, “Well, if you’re so concerned about us, why don’t you just go home and work against racism there?” And that changed me.

CATHY: It’s interesting what happens when we see our country through the eyes of others.

ANN: Absolutely. When I went home, I got a job teaching at a Black college in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and in 1968 Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis. The students were saying, “We have to march.” So we did. That was my first foray into the streets. We had students from the South, but we also had students that came from urban settings in the North. Very different students talking about what you can do when things are bad – the activist bent of the urban students, and the Southern Black kids saying, “Hey, you can get killed down here for that.”

I still wanted to do good in the world, but I wanted to have an impact and change systems and conditions. So I majored in Black studies – it didn’t have that name at the time – for my graduate work at Columbia. The Vietnam protests were going on. In New York I went to a lot of demonstrations, but I wasn’t an organizer. I didn’t start organizing until after I finished graduate school.

I went to Lansing, Michigan, and became director of the Lansing Area Peace Council [now the Peace Education Center of Greater Lansing]. We organized actions, demonstrations, civil disobedience for various things, like the grape boycott, the lettuce boycott, South Africa. The central focus was Vietnam. There were also local issues, like integrating the neighborhoods and ending redlining. I helped organize a school for high school dropouts, white kids and African American kids and Hispanic kids and Native American kids together in this school. It was a good time, a learning time.

CATHY: I remember the grape boycott, wasn’t that 1965? Or 1967? In 1967 I was only 14. I don’t think I really understood what it was all about. I hung around the fringes of it. But you have to start somewhere.

ANN: Absolutely. It was a good place to learn. Because the farmworker people, they had their game together.

“Women didn’t have a place at the table”

CATHY: Tell me about the advocacy you’ve done around violence against women and women in the skilled trades.

ANN: During Vietnam organizing, there was consciousness among women, recognizing that maybe they didn’t have a place at the table and in a lot of the decisions that were being made.

CATHY: Do you mean within the antiwar movement?

ANN: Sure. I went to a conference in Chicago organized by the Committee of Returned Volunteers. We were trying to say that perhaps the Peace Corps wasn’t where America should be putting their energy. And these guys [running the conference] were probably big names that you would know. But all of a sudden, the women in the room stood up and said, “We’re leaving. We’ve tried to say our piece, you won’t listen, and we’re going to the basement.” And all the women stood up and walked out. So I felt, well, I’ll go. And that was a beginning awareness, starting to see how to have a voice.

We organized women’s consciousness-raising groups in Lansing. Women would get together and talk about various issues, and you began learning about the abuse that some of them were experiencing. There were no laws or protection. One project we worked on was getting streetlights, because it was thought it would be safer for women. Then we decided that there needed to be a shelter. So we started the Council against Domestic Abuse.

Around 1975, I was teaching in a program for high-school dropouts. Most of the students could not afford to go to college, and they had no interest, particularly, in it. This was a time when women in labor unions were putting pressure on industry to allow women to get into the trades. We had vocational classes in the high school, but there were no girls in those, and there were very few people of color in them, if any. I started trying to get those young people involved in vocational classes. But they would go to these programs and run up against all the sexism or racism. It was discouraging for them. They weren’t being encouraged.

I got it in my head that I would get myself certified and I would teach them. A group of us organized ourselves, and we tried to get into the trades, and we couldn’t. We were being turned down left and right. So we filed a bunch of lawsuits.

CATHY: Turned down by whom?

ANN: The construction and industrial unions. Women in the UAW were also filing lawsuits. They weren’t getting in either.

CATHY: What trades did you try to get into?

ANN: Electrical and plumbing. Finally I was offered two apprenticeships – one in construction as a plumber-pipefitter and another at the General Motors Oldsmobile factory in Lansing. I decided on the factory. And I started on the path of being a pipefitter, and I earned my journeyman’s card. It was a very hard path. My dissertation was a feminist oral history about women in skilled trades in the auto industry, and the title of it is “Journeys of the Uninvited.”

I was in the factory for 20 years, and active in UAW Local 652, and we kept the support group going. We worked with the Labor Department and with schools and community colleges to try to change the way women were treated in trades education. Because if nobody teaches you how to use those tools, you can’t do the job. Six years later I got asked to work in the education department at General Motors. GM and the union were facing lawsuits, so they asked me if I would run some programs to upgrade skills and recruit people of color and women for the trades. It was a 20-year journey.

Activism in retirement

CATHY: Let’s fast-forward to the political advocacy work you’re doing now. When did you move to K?

ANN: We moved from Michigan seven years ago. I left a community in Lansing where I was active. We had been organizing around the Iraq war and Afghanistan, and I was working in my neighborhood on the Eastside of Lansing, developing health projects. We came here for the same reasons most people come here. We’re getting older. I’m a lesbian and my partner and I don’t have any children, so we came here knowing that we would need support. We wanted to be in a community that would be accepting, a progressive community. I was looking for people who shared my interest in community organizing, structural change, and anti-oppression work. Here at K we started an LGBTQ+ & Allies group. It wasn’t just around gay pride, it was around support and advocacy.

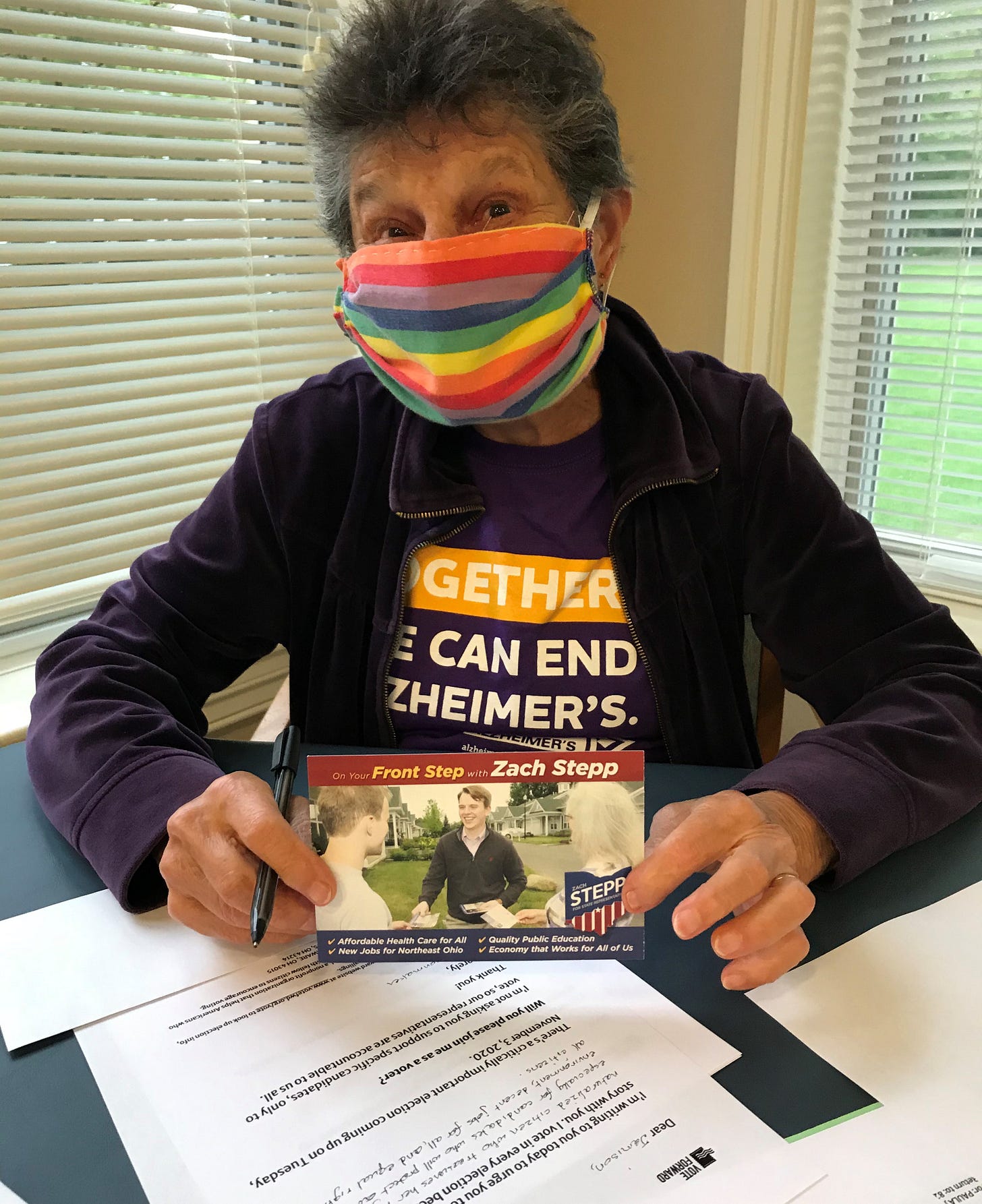

CATHY: Tell me about the postcards.

ANN: So here we are in covid, early 2020, and people are all staying inside their cottages. What could we do? There was a primary coming up, and we were geared up to go knocking on doors and do voter registration events in town. But then, bang! We couldn’t go outside. I started emailing people and saying, “Would you like to write letters and postcards? Would you like to make phone calls? There are some progressive candidates who could use our support. Would you like to help out?” And my email distribution list grew. It was an amazing response. People wanted to do something. Maybe I started out with 10 people and now there’s like 125 people on the list.

CATHY: There’s only about 325 residents at K, right? And you got 125 of them?

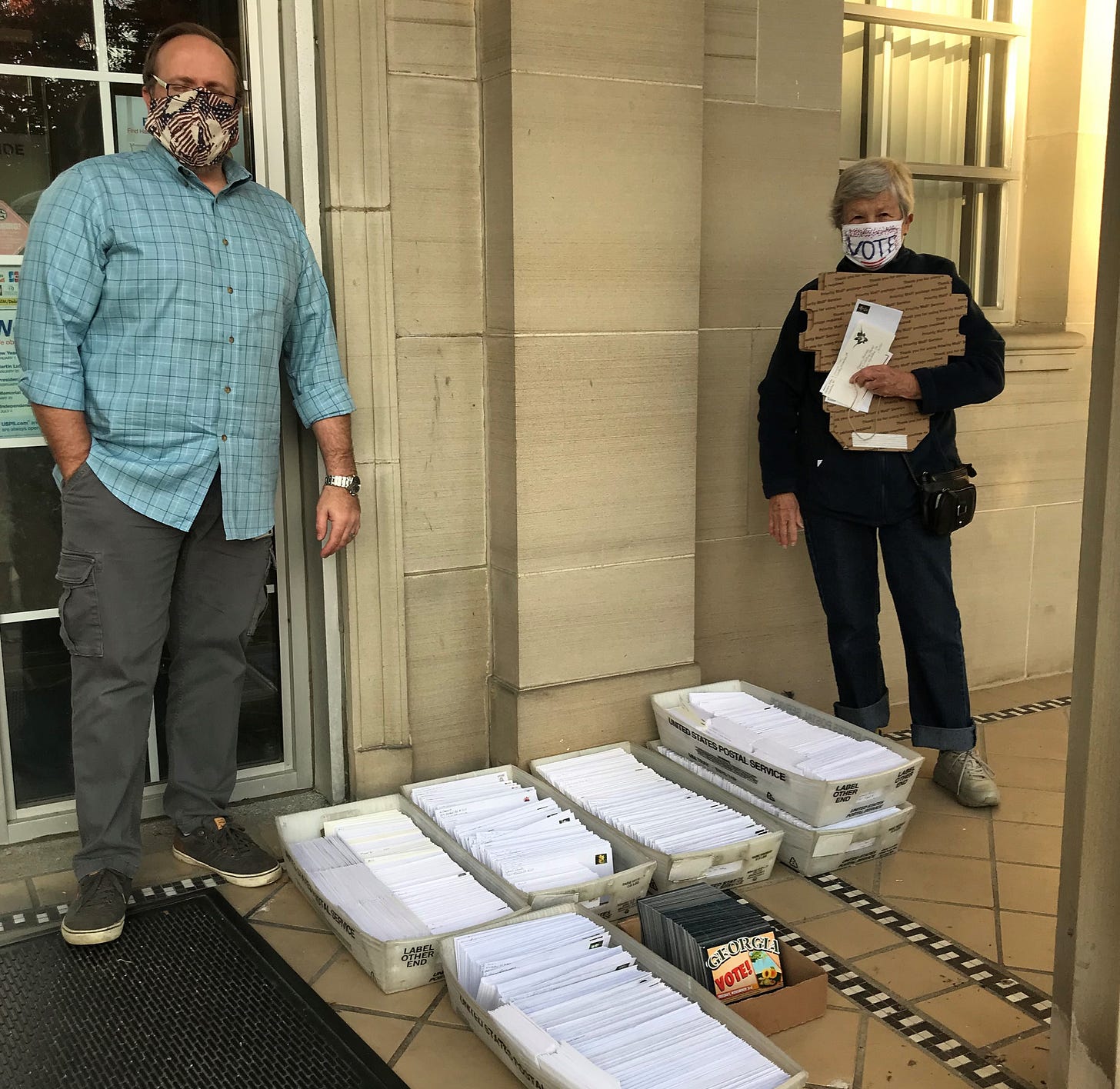

ANN: Yeah, easy, and probably more. Then K started allowing little group meetings of people, masked and socially distanced. You could come together in the meeting room if you sat six feet apart and you had a mask on. And I thought, well, crumb, we could go in there and sit six feet apart and write postcards and letters. There were people who have arthritis. They couldn’t do a lot of writing, but they said, “I can do stamps, I can do sorting.” Or I would deliver cards to folks and they would write at home. It just took off.

CATHY: What organizations were providing the postcards and addresses?

ANN: There was the League of Women Voters. There were candidates’ campaigns. We did Postcards to Swing States and almost 4,000 letters for Vote Forward.

CATHY: Have you done any canvassing with K folks?

ANN: Not since covid. Before, about eight of us were canvassing. Now I’m the precinct captain for the Democratic Party, and I’m hoping to organize canvassing again. We have a Senate race that’s really important, and the Ohio governor’s race and judges. I think people will want to canvass.

This is a community that is really interested and active in different ways. There was a request to find housing for asylum seekers, and again people rose to the occasion. We organized a blanket-washing brigade. Working with people from town, we formed a group supporting immigrants and asked for donations and volunteers. Two families now are being supported. We have an environmental group that’s active, going to demonstrations, writing letters to the editor, and doing educational programs.

CATHY: How does being an activist change when one gets into deeper old age? Do some activities become less possible? Do new possibilities open up that didn’t exist before?

ANN: It definitely changes. And probably at different touchpoints, depending on a person’s status. One thing that changes is your energy. I’m in pretty good physical shape, but I get physically tired much quicker. I can do 10 miles of canvassing, but that could wipe me out for a couple of days.

CATHY: I’m only 68, and I find canvassing physically exhausting.

ANN: You’re more careful about how you’re going to use your time, what you’re going to put your energies into. There are people who can’t canvass or write postcards and letters, but I think there are many ways to channel energy. There’s a lot of wisdom here, so you find people starting to write. Maybe you’re not the organizer anymore, but you look to support and mentor and be present for those who are organizing events. Words can make a difference. They’ve made a difference to me over the years. I look back at people who encouraged me at certain points when I felt hopeless.

Probably most important is not to lose interest. To follow what’s going on and encourage dialogue, so we can figure out who to vote for and what the issues are. We have to be awake. I think that one of the amazing things here, working with this community and with “old” people, if we want to put that label on it, is that it gives you hope. I think we gave that to each other. You laugh, and you keep doing just one more thing to make a difference. So that’s the joy of being together. Like I got to spend time with your dad. Look at that.

CATHY: You got my dad writing postcards. Look at that! Who would ever have guessed?

A 2010 interview with Ann about her peace and racial justice work is available on YouTube at https://youtu.be/eTpdjq98cA4.

Wonderful interview. Very true about Americans outside the country learning about what USA acutally does abroad while expressing the opposite. I loved that her students challenged her to go home and do something about racism in the US. Hurrah for her continuing activism, and getting togther to do separate tasks to get those letters and postcards out. Of course, your Dad was writing , but those that couldn´t saying ¨I can do stamps!¨